When disaster strikes: Anaesthesia in Nepal, by Chengyuan Zhang, 2015

Elective plans don't always work out. Mine had been tantalising me in the stressful run up to finals. Nepal offered me the experience of anaesthesia in a resource-poor country and the chance to escape to a new culture.

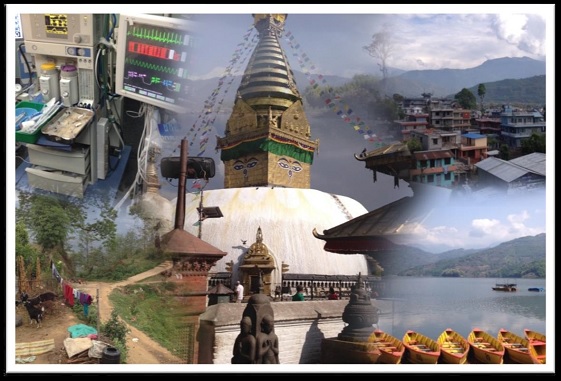

My Lonely Planet guide had promised me rare wildlife, ancient temples and adventure of a lifetime trekking. Little did I know that my elective would come to an abrupt end only three weeks in.

What strikes you, amid the sweltering heat, traffic congestion and pollution of modern day Kathmandu, is the kindness, friendliness and hospitality of the Nepalese.

In a city of temples and little streets filled with mopeds, perhaps the biggest draw is the people who live there. I was based at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, the largest tertiary centre in the country, built by the Japanese in the 1980s.

Unprepared

I had no clue what to expect but fresh from doing anaesthesia at UCLH, I certainly didn't come prepared. I didn't even pack any scrubs! I remember a handover from the night team. A patient with an acute abdomen was on the table for a laparotomy. The surgeon thought he could save her, the anaesthetist thought it was futile but being many years his junior, didn't feel like he could raise the issue.

By the time I was in theatre, she was severely acidotic with a dangerously low haemoglobin. Four empty glass bottles of 'normal' saline lay at the side, only worsening her acidosis. A single unit of blood and a noradrenaline infusion were all that prayed hard for a miracle that never came when she passed away on the open plan Intensive Care Unit.

There are huge challenges for anaesthesia in Nepal. Dedicated doctors are held back by outdated equipment and a limited range of available drugs.

Nepalese doctors would baulk at our medical waste. In Nepal, used airways are thrown into a tub of Fairy liquid and given a swill, ready for the next patient.

The learning curve is steep and trainees, often on 24 to 36 hour shifts, solo complex cases early on and complete their training in three short years. Nothing like our consultant-led culture here in the UK!

I would have loved to spend more time in such a friendly place where trainees insisted on buying me lunch and offered to get me hands on with the airway, at their own expense.

Earthquake number one

Unfortunately, while out trekking, I was caught up in a terrifying 7.9 magnitude earthquake which brought down several buildings before my very eyes.

People who already had very little were now left with nothing.

That night, with frequent aftershocks, nobody in the city slept well as people huddled outside in open fields. I went back to the hospital the following morning and quickly realised that despite my medical degree, there was little I could offer.

Faced with a language barrier and limited to paramedic roles, already filled by numerous Red Cross teams, I checked back in with my host family.

Earthquake number two

That afternoon, sitting in the second floor of a cracked building, earthquake number two of 6.7 magnitude hit and frightened, our group immediately took refuge in the British Embassy.

On our way, we passed displaced Nepalese families, now homeless, setting up camp in open fields with no water, little food and no toilet facilities.

Tucking into reconstituted ration packed food in the Embassy garden felt like a luxury in comparison. I also never imagined I would feel so out of my depth and pressed to make decisions before I'd even started my FY1 job.

However, after the only doctor from New Zealand left, I was called on a few times. Mostly, to manage pain in an elderly diabetic with a hip fracture. But one time, burning central chest pain, sweating, vomiting and left sided shoulder pain called too.

I can't say I wasn't glad when after four cold and wet nights, I was flown back in the early hours by a Foreign Office chartered flight, but I will be holding onto my Lonely Planet guide because I'm certain I will be returning sometime in the future.

I am thankful to the Association for helping to fund an eye-opening and at times heart rending experience which I will always remember. I am grateful to the Anaesthetics Department at TUTH for the wonderful but sadly short experience I had and to Dr Helgi Johannsson for following my earthquake tweets and letting me finish off my elective with plenty of hands on experience at St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington. I would also like to thank Dr Rob Stephens at UCLH for constantly inspiring students interested in the specialty.