Sir Ivan Magill: Anaesthesia After WW1

Sir Ivan Whiteside Magill (1888-1986) is one of the most innovative and well-known figures in modern anaesthesia. Initially an anaesthetist for surgeries on facial and jaw injuries after WWI, Magill pioneered new equipment and techniques that have been invaluable in the development of anaesthesia, including the Magill forceps, laryngoscopes and endotrachael intubation among many others.

Magill also helped to promote anaesthesia, encouraging colleges and societies to recognise the skills of anaesthetists and to see anaesthesia as a highly specialised field of medicine. He was instrumental in the foundation of the Association of Anaesthetists in 1932 and the Diploma of Anaesthesia in 1935.

This exhibition, first displayed at the AAGBI’s Annual Congress in 2013, presents some of the equipment developed by Magill.

Introduction

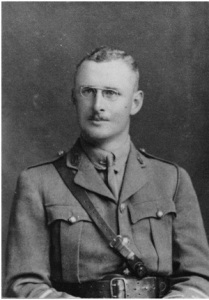

Born in Larne in Northern Ireland, Magill qualified in medicine from Queen’s University, Belfast, in 1913. After resident medical appointments he joined the Royal Army Medical Corps and served in France during the First World War.

Sir Ivan Magill in WW1

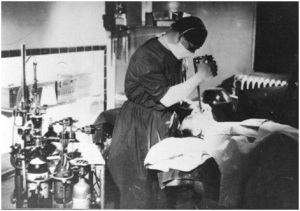

In 1919, pending demobilisation, Magill was posted to Queen Mary’s Hospital for Facial and Jaw Injuries in Sidcup. This was a special military hospital with an international surgical staff undertaking reconstructive surgery of war wounds including the pioneer plastic surgeon Major (later Sir) Harold Gillies. Magill’s task was to administer anaesthesia, even though he had very little practical experience in this. Generally, anaesthetics in this period were given using mask covering the nose and mouth, making operations very difficult for surgeon operating on the face and jaws. With Stanley Rowbotham, Magill developed wide-bore intubation and this procedure has since become essential practice for major operations of all categories.

Magill went on to become the leading exponent of anaesthesia for the developing specialty of thoracic surgery, and was an initiator and examiner for the Diploma in Anaesthetics from 1935. He anaesthetised King George VI for two major operations in the 1940s and was appointed a Commander of the Victorian Order in 1946 and knighted in 1960. He died, greatly honoured in 1986, aged 98.

Sir Ivan Magill: Intubation

One of the developments that Sir Ivan Magill is best known for is intubation. In 1919, Magill was posted to St Mary’s Hospital in Sidcup, a military hospital that specialised in facial and jaw injuries. Opened in 1917, by 1921 St Mary’s had treated over 5,000 servicemen from Great Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Because of the nature of these injuries, it was very difficult for the anaesthetists and surgeons to use the traditional anaesthetic face masks, and so Magill and fellow anaesthetist Stanley Rowbotham developed tubing for tracheal intubation. Using this technique, the anaesthetic gases could be delivered directly to the lungs, giving surgeons greater access to the face and jaw, and protecting them from ether exhalations of the patient.

Magill bought the first of the distinctive orange tubes from a football shop on Tottenham Court Road and found that the end of the coil of tubing had the curve needed for intubation. After this shop was destroyed in the Second World War, he worked with Charles King to manufacture the tubes.

Though both the nose and mouth could be used for intratracheal intubation, in an article from 1921, Magill notes that ‘the nasal route is even more useful… as it gives the anaesthetist that happy confidence in freedom of airway and the impossibility of blood getting into the trachea’.

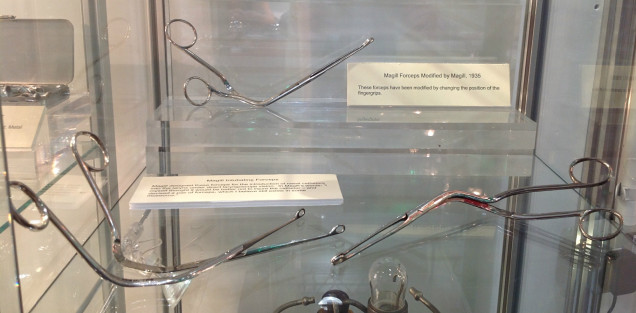

To prevent damage to the nasal catheters used for intubation, Magill also developed a pair of forceps in 1920. As well as preventing injury to the tubes, they also allowed the anaesthetist a better view of the larynx. Magill forceps are still occasionally used by anaesthetists today, and also by ENT surgeons as the narrow design is useful for removing foreign material from the inside the throat.

Apparatus

During his time at Queen Mary’s Hospital, Magill generally used a mixture of gas, oxygen and ether. In an article from 1910, he mentions that patients hated the smell of ether, so much so that a little ‘accidentally spilled in a ward is quite sufficient to put most of the inmates off their dinner’ and that ‘many men being retching immediately they enter the anaesthetic room’. To counter this, tinctures of lavender and bitter orange were put on the facemask and around the room, in an attempt to disguise the smell.

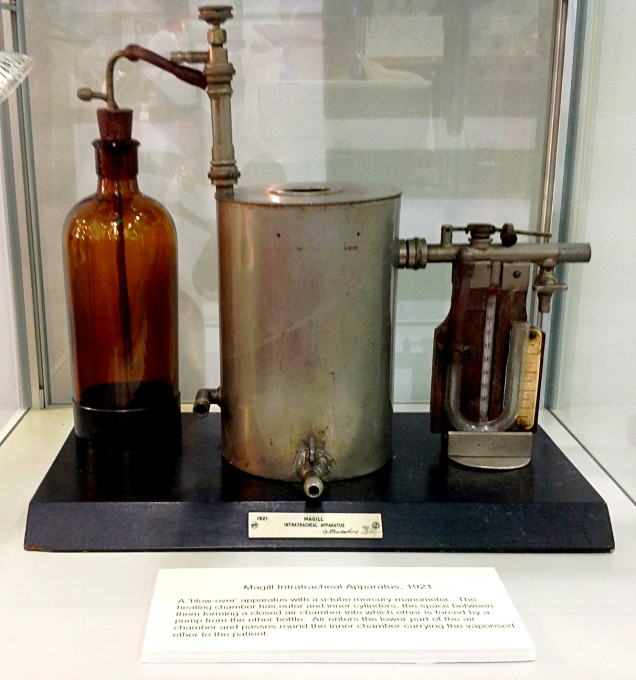

To deliver this mixture of anaesthetic gases, Magill developed a series of apparatus and worked on improving them over ten years.

The first example, from 1921, is a blow-over apparatus and contains a mercury manometer to measure the pressure. It has a heating chamber to warm the ether, with outer and inner cylinders, the space between them forming a closed air chamber into which the ether is forced by a pump from its bottle. Air enters the device through the lower part of the chamber and carries the vaporised ether from the inner chamber to the patient.

This modification of Magill’s 1921 design contains a second ether bottle and a water-sight flowmeter, with ether drop feed dome-shaped for better vision.

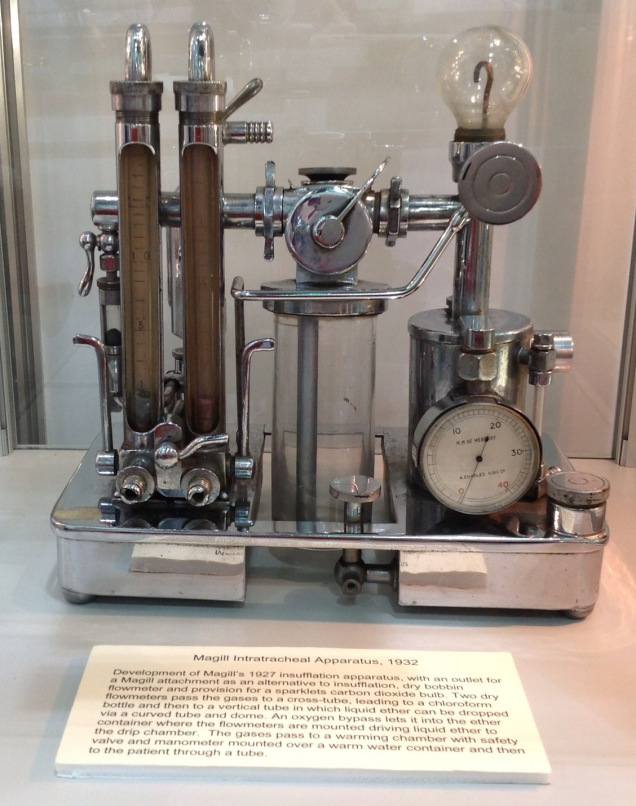

Magill had refined his design again by 1932. This apparatus included two dry bobbin flowmeters to measures the anaesthetic gases. These lead to a chloroform bottle and a vertical tube into which liquid ether can be dropped. The gases pass to a warming chamber with safety valve and manometer mounted over a warm water container and then to the patient through a tube.

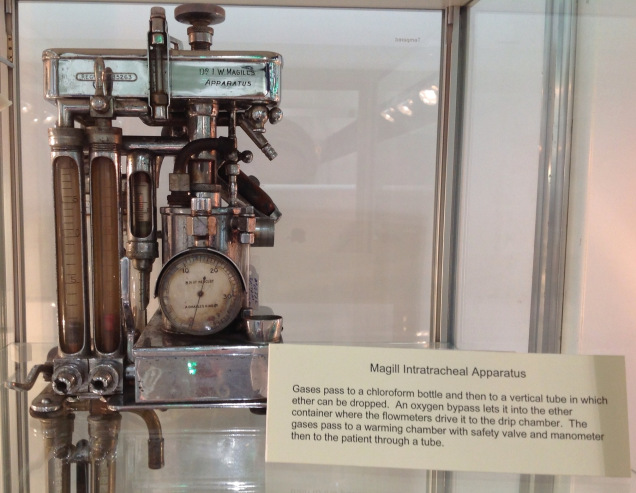

This device is similar to the 1932 model in that gases pass through a chloroform bottle and there is a vertical dropper tube for ether. It also contains a flowmeter and warming chamber with manometer that delivers the gases to the patient.