Out of Our Comfort Zone: Pain Relief in a Crisis

This exhibition was on display at the Anaesthesia Museum from July 2013 – July 2014. It celebrates the development of emergency pain relief and pays tribute to those affected by wars and disasters. The exhibition particularly focuses on the work of doctors, and especially anaesthetists, who deal with trauma and injuries sustained in wars and terrorist attacks.

Because of the nature of their work, anaesthetists are more likely to have the skills necessary to deal with this type of injury than any other doctor. Not only are they experienced in keeping patients safe during major surgery, they also are trained in resuscitation and often run intensive care units and pain clinics in hospitals. As a result they are trained to preserve life, prevent complications from injuries, and relieve pain. At the Moorgate train crash in 1975 for instance, in which 74 people were injured and 43 killed, 16 out of the 18 doctors on site, were anaesthetists.

The exhibition looks at pain relief in this type of disaster, as well as techniques used in war and terrorist attacks. It originally included an oral history interview with Dr Andrew Hartle, the AAGBI President, who treated casualties from the London 7/7 bombings.

History

The earliest recorded use of anaesthesia in war is during the Mexican/American War in March or April 1847. A senior American surgeon was critical of it and believed that it caused infection, impaired wound healing and caused coughing blood in patients with gunshot wounds. However, it was used successfully during the Russian campaign in the Caucasus between July and September 1847.

Baron Dominique Jean Larrey (1766-1842) stressed the need to treat and evacuate the wounded quickly. Unlike domestic disasters and acts of terrorism, wounded soldiers sometimes have to travel long distances when they are evacuated. Larrey treated wounded soldiers regardless of rank or which army they were fighting for.

Baron Dominique Jean Larrey

During the First World War, the Royal Army Medical Corps was expanded and specialist anaesthetists worked at casualty clearing stations. Though the role developed as a specialism throughout the war, anaesthetics were also administered by other doctors, nurses and sometimes priests- often whoever was close by.

In 1940, civilian air raid casualties were rarely given morphine. However, soldiers wounded in Italy were given morphine during their long evacuation. An initial report of 1948 suggested that morphine and anaesthesia could be given to wounded soldiers but in 1950 this advice became much more cautious: no spinal anaesthetics should be given and skilled administration of anaesthesia was needed. The sudden attack on Pearl Harbor and the lack of facilities and trained anaesthetists to treat casualties, led to the comment that more servicemen died as a result of receiving thiopentone than were killed by the Japanese. This idea has since been refuted.

An Australian medical officer treats a wounded soldier at an Advanced Dressing Station in the Third Battle of Ypres, 1917, (C) IWM E (AUS) 714

Pain relief was not always given because of fears that it could lead to morphine addiction.

Before 1960, seriously injured people received little or no life-supporting treatment before arriving at hospital. Modern resuscitation methods had not yet been developed, and there was less training for emergency workers. Even as late as the 1980s, pain relief was discouraged because of problems in delivering it. Anaesthetists argued that it was essential on both scientific and compassionate grounds.

Terrorist Attacks of 7/7

There was no warning of the terrorist attacks that occurred on London’s Underground and buses on the morning of 7 July 2005.

When the bombs were detonated the small amount of solids they contained were converted into enormous volumes of gas and there would have been an almost instantaneous rise in the atmospheric pressure at the site of the bomb. A pressure wave would have travelled out and it would have rebounded off walls, floors, ceilings etc. People who were near to the bomb received devastating injuries. The pressure wave would have been partly reflected and partly absorbed by the bodies of people further away. Those people received less serious injuries.

Damaged ear drums and tinnitus would have been experienced by many people and they might have experienced lung problems. Burns too can be caused by the rise in temperature which results from the chemical reaction of the exploding bomb. Foreign body injuries can be caused by the bomb casing which is propelled out at a very high speed.

In January 2013, it was reported that engineers at Newcastle University have developed blast-resilient carriages. These aim to reduce blast impact and debris that maims and kills.

The unexpected nature of this attack and the severe injuries that resulted from it, tested London’s emergency services. Please listen to our oral history interview with Consultant Anaesthetist, Dr Andrew Hartle, who helped to deal with the aftermath of the bomb that exploded in a Circle Line underground train at Edgware Road.

Pain Relief During War

Original Clover inhaler

Clover inhaler, modified by Hewitt

Clover Portable Regulating Inhaler, 1877 & Hewitt’s Modification, 1901

This was the first inhaler that easily regulated the amount of ether vapour inhaled and was very popular. Invented in 1877, it was still used during the First World War. The design was modified by Hewitt in 1901 to improve patient comfort and ease of use for the anaesthetist.

Ether

Said to have been discovered by Raymundus Lullius in 1275 and named ‘sweet vitriol’, ether was one of the first anaesthetic agents to be discovered and was used until well into the twentieth century.

Schimmelbusch Mask

The standard mask for early anaesthesia, the Schimmelbusch has a gutter around the edge to collect the anaesthetic liquid, preventing it from touching and irritating the patient’s face or eyes. Though a basic design, there are many variations to the Schimmelbusch mask: the Anaesthesia Museum has over 40 examples, all of which are slightly different.

Ethyl Chloride

Ethyl chloride was first made in 1759 by Guilliaume Rouelle, and was first used as a general anaesthetic in 1848 by Heyfelder. This example is a spray from 1953 and contains the liquid at a slight pressure as it becomes a gas at room temperature.

Junker’s Inhaler, Modified by Buxton

Created in 1892, this design had a larger bottle than Junker’s original. The face piece is hinged to keep lint in position over the patient’s nose and mouth

Shipway Warm Ether/Chloroform Intratracheal Apparatus

This apparatus was created in 1916 during the First World War. Shipway believed that warm ether vapours were better for the patient and more beneficial to inhale.

Boyle’s Nitrous Oxide/Oxygen/Ether/Chloroform Apparatus

Produced in 1926, almost ten years after Boyle’s original design in World War One, this apparatus has three bottles with bubble sight meters, five filler inlets with corks and a large-bore mixing tube connecting the bottles to mix the anaesthetic agents.

Fentanyl (Sublimaze)

Fentanyl is a potent, synthetic analgesic and has been in use since 1960. It was used for pain relief in the Falklands War.

Papaveretum (Omnopon)

Omnopon is a powerful opiod analgesic and is used for moderate to severe pain. It was used for pain relief during the Falklands War.

Pain Relief During War and Emergencies

Flagg Can

The Flagg can is a very simple ether vaporiser, and could be made out of a tin can. Vapour strength could be controlled by varying the air entry. It was invented in 1916 and was used in both the First World War and the Spanish Civil War.

Sodium Thiopentone (Pentothal)

This drug was discovered in the early 1930s by two scientists at Abbott Laboratories. It is a rapid onset, short acting anaesthetic and was manufactured by Abbott until 2004. It was used in World War Two to treat people injured in the Pearl Harbour attack, and has subsequently been used as a truth serum.

The Triservice Apparatus

This apparatus was designed by Brigadier Ivan Houghton in 1981 as a development of the Oxford miniature vaporiser. It is designed to be portable and robust enough to be parachuted to ground troops. It does not require any extra equipment and is simple to put together. The triservice was the only anaesthetic apparatus used on land in the Falklands War, and has been used by the military and in major disasters.

Pain Relief in Emergencies

Morphine

Morphine was first isolated in 1804 by Friedrich Sertürner in Germany and distributed in 1817. It was more widely used after 1857 and the invention of the hypodermic needle. It was originally named morphium by Sertürner after Morpheus, the Greek god of dreams and used as a substitute for those addicted to opium or alcohol, until doctors realised that it was more addictive than either of these substances. Preloaded syringes have been used to give pain relief in emergencies and can be used in hospitals to relieve the pain of a heart attack.

Methoxyflurane (Penthrane)

First used in surgical anaesthesia in 1960, it can also be used as an analgesic. Ambulance teams in Australia use this drug as a self-administered analgesic with those with traumatic injuries. It is no longer used as an anaesthetic as prolonged inhalation of high concentrations produce renal problems. This is an example of methoxyflurane as a self-administered analgesic. It is single-use and disposable and used to inhale penthrane. Blocking the opening near the mouthpiece increases the intensity and deepens the analgesia.

Cardiff Inhaler

This inhaler is a modified Tecota Mark VI trilene inhaler. It was introduce into clinical use in 1959 and this example dates from 1959-1979. It could be used in intensive care and obstetrics.

Ketamine (Ketalar)

Ketamine can be used as both an anaesthetic and an analgesic and was developed by Parke-Davis in 1962. It was given to American soldiers in the Vietnam War and was also used in both the Falklands War and the first Gulf War. It is particularly useful as an emergency anaesthetic as it does not supress the patient’s airway to the degree of some other agents, and so patients may be able to breathe by themselves without additional airway or ventilation equipment. However, it has been noted that it can cause hallucinations when used as an analgesic or sedative.

Trichloroethylene (Trilene)

Trilene’s anaesthetic properties were first described in 1911 and it was used as an anaesthetic from 1935 until the 1980s, particularly in obstetrics. It was first made in 1864 by German scientist Emil Fischer. Since then, it has had a number of other uses including cleaning and degreasing rocket engines, decaffeinating coffee and dry cleaning. It was found to be a carcinogenic.

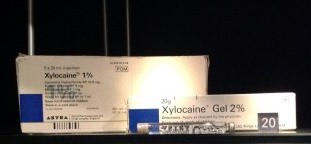

Xylocaine

Xylocaine is also known as Lidocaine and is a local anaesthetic which can be injected or applied as a gel to the skin. It was first created by Nils Lofgren in 1943 and was marketed from 1949.

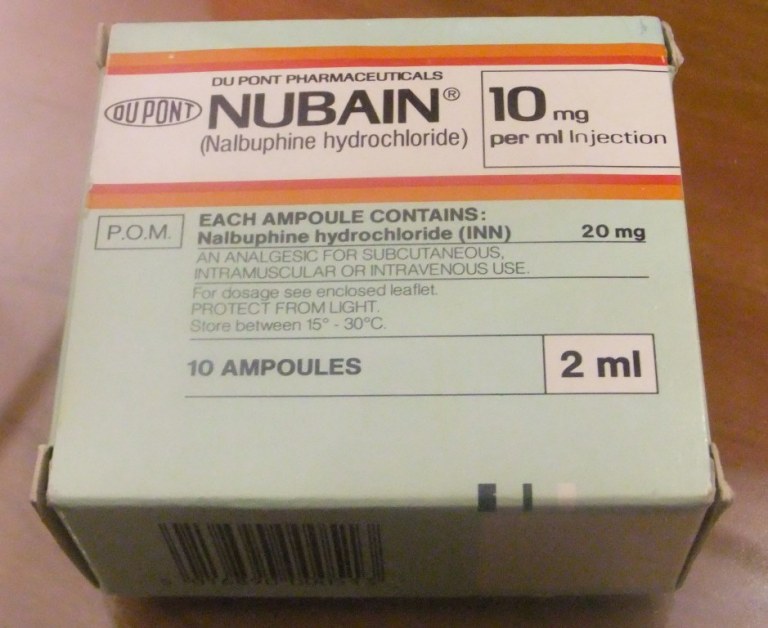

Nalbuphine (Nubain)

This can be used as an analgesic for moderate to severe pain, and can be used for postoperative pain, obstetrics and to supplement other drugs in producing general anaesthesia. This example was sold after 1978: it is no longer used in Britain and has been removed from the British National Formulary.

Pulse Oximeter

The oximeter was invented in the 1940s and the pulse oximeter manufactured from 1979. The monitor uses red and infrared light to measure the amount of oxygen in a patient’s blood: red light is absorbed by oxygenated blood and infrared by deoxygenated, and this is measured by the monitor on the patient’s fingertip. This example was manufactured by the charity, Lifebox, which works to provide equipment for operating rooms worldwide.

Entonox

Entonox is a 50/50 mixture of nitrous oxide and oxygen and is used as an analgesic. As it is known to be reasonably safe, it is used in emergencies, in dentistry and as a self-administered analgesic in obstetrics. This examples dates from 1963 and is designed to be portable.