Doctor says relax

The Amazonian arrow poison that revolutionised Anaesthesia

The Anaesthesia Heritage Centre has opened a new temporary exhibition on muscle relaxants. It showcases authentic curare weapons alongside anaesthetic equipment to tell the history of muscle relaxants in the practice of anaesthesia.

Curare is a deadly poison found in the Amazonian Basin of South America. When injected into the bloodstream it acts as a muscle relaxant which paralyses and asphyxiates prey.

Tribal elder Binan Tukum hunting with his son for monkeys in the rainforest. Copyright: Lazlo Mates

Curare was the first muscle relaxant (or neuro-muscular blocking agent) to be introduced into western medicine. It revolutionised the practice of anaesthesia and allowed life saving operations, which were previously considered too dangerous, to be performed for the first time.

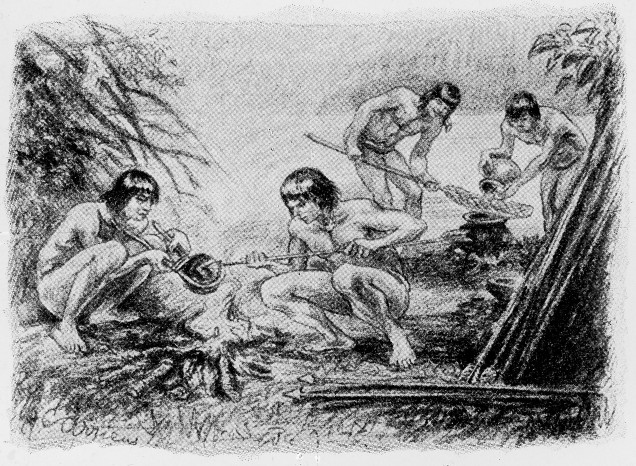

South American tribes will shoot curare coated darts or arrows from blow pipes and bows to kill or stun animals for food and clothing. The process of mixing the curare poison and creating weapons is a highly skilled process. Different strengths of poison are needed for different sized prey, and mixing these accurately can only be determined by taste; curare is not toxic through ingestion alone.

South American Indians preparing curare. Wellcome collection

Arrow poison has been known to Europeans since Sir Water Raleigh’s expeditions to Guyana in 1595. It was first brought back to England in the 1760s by Edward Bancroft (1741-1821) who had encountered the poison during his time in Guyana writing ‘An Essay on the Natural History of Guiana in South America’.

Naturalist Charles Waterton (1782-1865) brought curare samples, or ‘woorali’ as he called it, back to England in the early nineteenth century and conducted experiments on animals. Alongside Benjamin Collins Brodie (1783-1862), Waterton administered woorali to a she ass whilst ventilating her with a bellows until the poison wore off.

After Waterton’s experiments, more scientific work was conducted by physicians of the nineteenth century. It was Claude Bernard’s (1813-78) experiments on frogs in 1844 which showed conclusively that curare was acting as a muscle relaxant. He noted that “it is an anaesthetic agent only in appearance. The animal feels, but cannot show it”.

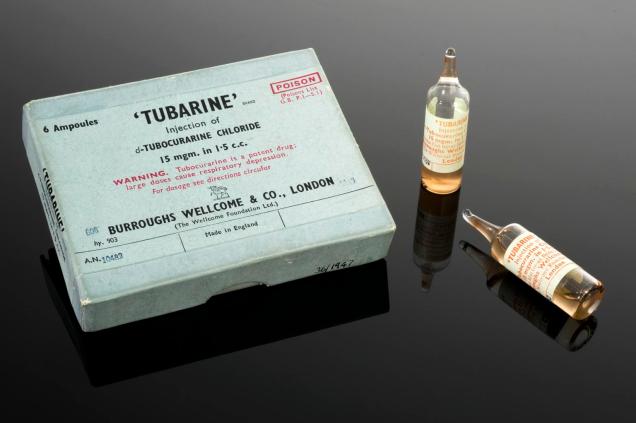

It wouldn’t be until the 20th century that the successful use of curare as a muscle relaxant in surgery was documented. The first recognized success was in North America by Harold Griffith and Enid Johnson, who used the preparation of curare, Intocostrin, during an appendectomy in 1942. In Britain, Cecil Gray found Intocostrin unreliable and instead popularised the use of d-tubocurarine chloride which was more consistent in its potency. D-tubocurarine would become the muscle relaxant of choice until curare-like synthetic agents replaced natural curare from the 1980s onward.

Tuburine ampoules and packed. Science Museum

Before the advent of curare in the 1940s, in order to achieve muscle relaxation anaesthetists would have had to administer a very deep ether or cyclopropane anaesthesia which could cause a number of heart, liver or kidney complications.

Additionally, with the total paralysis of a patient’s diaphragm, these surgeries were only possible with the invention of tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation of the lungs. Now, with thanks to muscle relaxants and manual ventilation, life saving heart, brain and thoracic surgeries can be performed.