A Silver Lining Through the Dark Clouds Shining: Marshall vs Boyle

From 1912, anaesthetics were included in the curriculum of all medical schools. However, when Great Britain entered the First World War on 4th August 1914, the role of an anaesthetic specialist was not recognised.

During the War years, this changed and specialist anaesthetic posts were created in the military in 1916. The change was driven by the death of nine million people during this global conflict and an unprecedented number of wounded. The training these anaesthetists received is unclear.

The provision of pain relief and anaesthesia was crucial. At the start of the War nitrous oxide and oxygen anaesthesia was in its infancy. This is the way wounded soldiers received treatment:

Evacuation to regimental aid posts

Sent to advanced dressing stations or field ambulances

Sent to casualty clearing stations in ambulance convoys

Evacuated to a base hospital by train or barge

Transferred to the UK on a hospital ship

>Every hospital that could, received casualties and extra hospitals were set up in universities, schools and stately homes.

Who Invented the Machine?

Since the production of the first Boyle’s Machine its name has endured. Its continuous development means it is still available today.

Although the machine bears Boyle’s name, many believe that it was invented by Marshall.

|

Geoffrey Marhsall

|

Henry Boyle

|

|

|

|

| Marshall qualified in medicine in 1911. He was interested in respiratory physiology.

|

Boyle qualified in medicine in 1901. He was interested in anaesthetics.

|

|

|

|

| Marshall joined up at the outbreak of the First World War and served in France.

|

At the start of the First World War, Boyle joined the Royal Army Medical Corps but did not serve abroad. He treated soldiers in British hospitals.

|

|

|

|

| In 1915 Marshall went to a Casualty Clearing Station to help reduce the mortality rate of soldiers suffering from shock many of whom needed amputations.

|

By 1917 Boyle reported on 1,000 cases of nitrous oxide and oxygen with ether or chloroform.

|

|

|

|

| Marshall designed a machine and asked a tinsmith in France to make it. He took his drawings to Coxeter when he was on leave. Marshall reduced the mortality rate from 90% to 25%.

|

Boyle met Gwathmey in 1913 and was influenced by him. But by 1917 he was dissatisfied with Gwathmey’s apparatus.

|

|

|

|

| Coxeter urged Marshall to publish his apparatus. Some say the drawings had been ‘borrowed’. Marshall published his apparatus in 1920.

|

Historians have suggested that it was Boyle who borrowed Marshall’s drawings. Boyle published his machine in 1919 and thanked Marshall for his help and suggestions for alterations.

|

|

|

|

| Marshall wanted to be a physician not an anaesthetist.

|

Boyle continued to improve his machine and became a renowned anaesthetist.

|

Anaesthesia During the First World War

Gwathemey Apparatus

Gwathmey developed this apparatus while with the American Red Cross. It has yokes for two cylinders of nitrous oxide and one of oxygen. It is controlled by a needle valve and tubes take gases to the bottle cap.

Marshall nitrous oxide oxygen ether apparatus

Geoffrey Marshall developed an anaesthetic apparatus based on a machine designed by Gwathmey. It gave gas, oxygen and ether and had flowmeters. It became the standard model in Royal Army Medical Corps practice.

Boyle apparatus

This is Boyle’s original nitrous oxide/oxygen/ether apparatus which closely resembled those of Gwathmey and Marshall. British gas cylinders would not easily fit Gwathmey’s apparatus and so Boyle modified it to produce this machine.

Ether & Chloroform

Ether

Ether was discovered in 1275 by Raymundus Lullius and called Sweet Vitriol. In 1540 Valerius Cordus described how to make it and Paracelsus discovered its hypnotic effects. In 1730 A S Frobenius called it ether.

Chloroform

Discovered in the 1830s, the anaesthetic properties of chloroform were not realised initially. Liverpool chemist David Waldie, suggested chloroform to James Young Simpson, Professor of Obstetrics in Edinburgh as an alternative to ether. On 4 November 1847 after supper, Simpson and his colleagues inhaled chloroform. Four days later, Simpson used it to relieve labour pain in his patients. It was quickly taken up in other areas of medicine and became part of the standard issue British Army medical kit in the First World War.

Schimmelbusch facepiece

This was the first mask with a gutter around the rim to collect liquid anaesthetic agent and stop it running down the face irritating the eyes and skin. It became a standard mask.

Symons drop bottle

Early anaesthetics were often given by the ‘open’ drop method. The patient inhaled vapour from a handkerchief on which the agent was dripped from a bottle such as this. This was particularly useful in situations where vaporizers were impractical such as wartime.

Pain Relief

Nitrous oxide and oxygen came in cylinders. Metal was needed for munitions and was therefore in short supply. Obtaining a supply of nitrous oxide was therefore difficult.

Nitrous oxide cylinder

Nitrous oxide was used during the First World War (often without oxygen) for short operations. It could be used by skilled administrators with local anaesthesia for abdominal surgery and high leg amputations.

Oxygen cylinder and gauge

Oxygen was discovered by Joseph Priestley in 1774. Modern medical use of oxygen became more popular in 1917 due to the work of J S Haldane.

Morphine tabloids

First isolated in 1804 by Friedrich Sertürner in Germany and distributed in 1817. It was more widely used after the invention of the hypodermic needle in 1853. It was used to treat wounded soldiers in Advanced Dressing Stations during the First World War, and was developed for self-administration in World War Two.

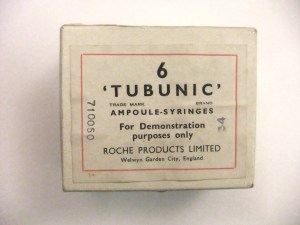

Tubunic Omnopon (Papaveretum)

First produced in 1910, this derivative of morphine, omnopon is a powerful analgesic. In the First World War, it was given to wounded soldiers suffering from shock in Casualty Clearing Stations.

Inhalational Anaesthesia

Mason mouthgag

This was designed for operations on the mouth. It has thick jaws which fit securely between the molar teeth, and is inserted once the patient’s muscles are relaxed.

Doyen mouthgag

This fitted closely to the cheeks making it possible to administer gas or ether whilst it was in position. It includes the addition of side tubes for chloroform.

Clover inhaler

This apparatus had a bag connected to the ether vessel and to the face piece. There is a tube inside. The regulator determines if the patient breathes into the bag or through the tube and ether vessel.

Junker inhaler modified by Buxton

This had a larger bottle than the original. A face piece with a metal rim carried the air supply into a perforated tube running from back to front of the metal frame. Lint could be put on the mask.

Ombredanne ether inhaler

This inhaler’s prototype was made from jam tins. The ether container held soaked sponges. Ombrédanne believed the rebreathing bag might help anaesthesia because it contained carbon dioxide. Small amounts of air were also admitted.

Shipway’s warm ether/chloroform apparatus

Shipway believed that warm anaesthetic vapours were better for the patient and more pleasant to inhale. This apparatus originally had a hand bellows.

Saline infusion set

The development of saline infusion was stimulated by war experiences. Saline was first used to treat the shock of cholera by Thomas Latta in 1832. A lot of saline infusions were given subcutaneously and rectally.

About

A Silver Lining Through the Dark Clouds Shining was the first in a series of four exhibitions commemorating the work of medical teams in the First World War. It was displayed in the Anaesthesia Heritage Centre from July 2014- July 2015.

The next exhibition, The Riddle of Shock, explored the development of treatments for shock, and the medical equipment and techniques available to surgical teams faced with unprecedented numbers of casualties.

The Anaesthesia Heritage Centre is open weekdays 10.00-16.00. Admission is free. For more information, visit www.anaesthetists.org/Home/Heritage-centre/.