#KnockItOut – tackling workplace bullying, harassment and undermining

What is bullying?

“You must be aware of how your behaviour may influence others

within and outside the team”

states the GMC's good medical

practice document, our professional code of conduct [1]. How

we behave whilst at work affects those around us, but this may

be easy to forget in the heat of the moment. Examples of

unprofessional behaviours such as rudeness, incivility, belittling

and humiliation are frequently found in most hospitals.

Medicine

has a traditional, hierarchical culture, and this may lead to those

in positions of power misusing their status and/ or shielding

such perpetrators of bad behaviour from censure. When an

individual uses their positional power in a way that leaves the

victim(s) feeling hurt, angry or powerless, this is bullying [2].

Social bullying involves unacceptable jokes related to protected

characteristics (e.g. gender, race), public insults, practical jokes,

slander and exploitation [3]. The line between ‘banter’ and

bullying can be a fine one, and it is the perception of the victim

that defines bullying, not the intention of the perpetrator [2].

Does bullying and harassment occur in the NHS?

One fifth of NHS staff reported experiencing bullying and

harassment by colleagues in last year’s NHS staff survey.

Unrealistic time pressures, staffing shortages and stress were

identified as factors contributing to bullying behaviour [4]. This

survey looked at all NHS staff, but is this specifically a problem

amongst medical staff?

The 2017 BMA survey of 7887 doctors found similar results [5, 6].

Twenty percent reported being subjected to workplace bullying

or harassment, and 39% identified that bullying, harassment

or undermining behaviour had occurred where they worked.

This suggests that being a bystander to an incident of bullying

or harassment is common amongst doctors. The survey found

bullying affects consultants and trainees fairly equally, with

disabled, LGBT and BAME doctors reporting higher levels.

When asked,

“Why do you think there is or may be a problem

with bullying in the NHS?”

familiar themes included staff under

pressure, difficulty in challenging poor behaviours from seniors,

and a lack of management commitment to tackling bullying.

A

lack of clarity as to what is acceptable behaviour, and a lack of

clear reporting procedures, were also felt to contribute.

More recently the incidence of bullying amongst non-training grade doctors has been highlighted, with 30% of SAS doctors

and 23% of locally-employed doctors reporting they had been

bullied, undermined or harassed at work in the last year [7].

Rudeness, incivility, belittling and humiliation were the most

common types of undermining behaviour reported. When

bullying relating to protected characteristics was reported, race

was the most commonly cited factor.

Do we have a problem with bullying and unprofessional behaviours in anaesthesia?

Specialty specific data is surprisingly difficult to come by. The

most recent GMC national training survey that had a specialty

breakdown of bullying and harassment was in 2017 [8], reporting

that 4.6% of anaesthesia trainees described experiencing, or

witnessing, bullying and harassment at work. This is a lower

incidence than that reported by our surgical trainee colleagues,

where 8% of surgical respondents and 11.2% of obstetrics

and gynaecology respondents reported being victims of, or

witnessing, bullying and harassment. While it may not be an

overwhelming problem in anaesthesia, it is plausible that we

are frequent observers of bullying and undermining in other

staff groups through our multi-disciplinary working environment

in theatres and on the labour ward. We are working with the

psychology research team at Northumbria University on a

project to study trainee anaesthetists’ experiences of witnessing

workplace bullying to investigate this further.

What are the effects of bullying in healthcare?

Research has demonstrated that merely witnessing incivility and

unprofessional behaviours can cause a performance decrease

of 20%, and worryingly this incivility can spread, with witnesses

being less helpful to others even if they are unconnected to the

event [9]. Exposure to bullying, either as a victim or bystander,

is also associated with negative job-related and health- and

wellbeing-related outcomes. There is an increase in mental and

physical health problems, symptoms of PTSD, burnout, increased

intention to leave the organisation, reduced job satisfaction,

and organisational commitment. Workplace bullying is also

associated with employee absenteeism, negative performance

self-perception, and poor sleep [10].

There are serious effects on patients too; in NHS organisations

where staff surveys report bullying, patients are less likely to

report being treated with dignity and respect [11]. There is a

strong association between bullying and the occurrence of

adverse events and compromised patient safety [12]. Indeed,

in his public inquiry into the failings at Mid-Staffordshire, Robert

Francis QC wrote;

“The common culture of caring requires a

displacement of a culture of fear with a culture of openness,

honesty and transparency, where the only fear is the failure to

uphold the fundamental standards and the caring culture”

[13].

Going beyond the individual health and wellbeing, the financial

cost of bullying is huge. These can be measured in terms of

sickness absence, employee turnover, diminished productivity,

sickness presenteeism, compensation, litigation and industrial

relations. A conservative estimate of the cost of bullying to the

NHS is £2.28 billion per year [14].

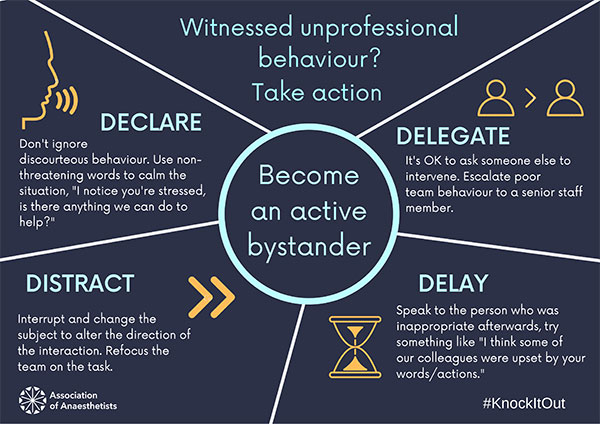

#KnockItOut

Through our #KnockItOut campaign, we want to change our

workplace culture to one that is free from bullying, harassment

and undermining behaviours. Whilst we endeavour to create

a compassionate culture, we need all our staff members to

be able to respond in constructive ways when they witness

unprofessional behaviour. We want to give them the tools to

confidently and successfully challenge these behaviours when

they see them. The active bystander approach has been used

in several anti-bullying and anti-sexual harassment campaigns

[15] – see Figure 1 for our version. Providing bystanders to an

incident with a framework to intervene safely is an important part

of changing the culture around bullying.

Being witness to a bullying incident can be frightening or

unsettling. There are times when reacting immediately may

involve being dragged into an argument, or cause further

unproductive behaviours. Taking a brief pause, recognising the

situation, responding constructively, and aiming for a measured

approach can help defuse the incident. We recognise that ‘one

size does not fit all’ in difficult situations, and aim to provide a

range of options to enable staff to intervene where appropriate.

We also recognise that one’s place in the organisational

hierarchy may alter how able one feels to challenge poor

behaviours; a junior staff member may well feel more able to

delegate to a trusted senior colleague in, or after, the moment.

The environments that we work in are increasingly stressful

places, making negative and unprofessional behaviours more

likely. Sometimes

declaring that you are aware of the situation, "I

notice you are a bit stressed, what can we do to help?",

will allow

the person under stress to ask for quiet, or perhaps assistance.

An indirect intervention by

distraction can be useful to change

the focus of the interaction, and to refocus on the task at hand.

Finally, the situation may not be suitable to be addressed in

the moment; in certain circumstances a

delay may be required.

Once the stressful situation has settled, speak to the person

who was inappropriate, stick to the facts as they happened, and

highlight how their words or actions were perceived by others.

In addition to providing intervention strategies, we want to

encourage a ‘SAFER’ space at work, where kindness and civility

are paramount, and staff work together towards a shared goal.

This can include engaging the team in a verbal run through of

likely stressful points in the day and how best to respond

“When

we get to the anastomosis can we turn the music off and have

quiet in theatre, please”

or “I’m expecting a challenging airway,

so can we not be interrupted during the intubation process,

please”

(Figure 2).

The Association of Anaesthetists is a member of the NHS

anti-bullying alliance, and by working together with the other

organisations involved we want to tackle the cultural and

systemic issues that contribute to bullying. It is time for us to

demonstrate as a profession that we are committed to change

and we will not tolerate unprofessional behaviour: it is time for

anaesthesia to #KnockItOut.

Roopa McCrossan

Association of Anaesthetists Trainee Committee

Locum Consultant in Anaesthesia, Freeman Hospital; Newcastle

Karen Stacey

Elected member, Association of Anaesthetists Trainee Committee

Locum Consultant Anaesthetist, Imperial College Healthcare NHS

Trust

Twitter: @RooMcCrossan; @karenstacey82