Personal protective equipment, Public Health England and COVID-19: ‘Montgomery in reverse’?

This article will be published in the June issue of Anaesthesia News

Concerns around personal protective equipment (PPE) availability are headline news. The Health Secretary’s comment that ‘some staff may be mis-using’ PPE received sharp rebuke from the Royal College of Nursing. Public Health England (PHE) has struggled to offer consistent guidance on which type of PPE to use, and this in turn has led to some of the Royal Colleges issuing their own variant guidance. All this reflects difficulties in understanding some of the core issues.

Statistics: the reality

The truth is that the issue about PPE is fundamentally a statistical question. There are three variables determining the chance that a healthcare worker might catch COVID-19 from a patient, each of which confers risk in a non-linear way:

- The contagious risk presented by the patient (in part dependent on their COVID-19 status, but also on their symptoms and stage of illness, etc).

- The degree of protection offered by any given form of PPE (a simple plastic apron to a full costume of the type worn in Ebola outbreaks).

- The degree of risk from any given activity (walking along a ward does not carry the same risk as tracheal intubation).

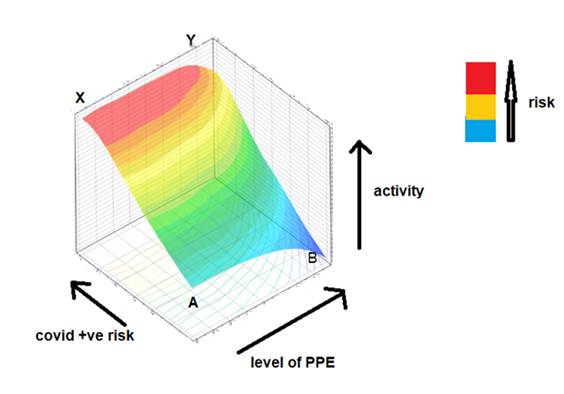

The challenge for PHE has therefore been to map these three variables to the aggregate risk, and communicate this meaningfully. Although difficult, it can be estimated statistically. What results is a 3-dimensional risk plot (Fig. 1), akin to a ‘response surface model’ in pharmacology.

The plot reflects our intuition in a complicated way. Wearing little or no PPE whilst undertaking exposure-prone tasks in a very contagious patient is likely to be very risky (point X; red zone). The same setting results in reduced, but not zero, risk (Y; orange/yellow zone) if wearing full PPE. The very low risk of walking along a ward (A; blue zone) could be reduced even further if wearing full PPE (B; also blue), but the relative risk reduction is small. Note that even full PPE in high risk scenarios is not without risk, as it relies on complete compliance in doffing, etc. While the plot may reflect reality, it is not actually very helpful as it is difficult to communicate the risks involved in plain language.

Figure 1. Schematic three-dimensional plot of risk (in colour) as related to: ‘COVID +ve’ (here the contagious risk from the patient, regardless of their actual ‘test’); level of PPE; and nature of the activity (from low- to high risk tasks).

Moving away from statistics: the ethical dimension

Personal perspective is more important than statistics, and the perceived risk-benefit balance is important to an individual. The Supreme Court has already clearly ruled on this, in relation to patient consent, in Montgomery vs. Lanarkshire Health Board. In brief, Mrs Montgomery faced a choice between vaginal delivery and caesarean section for her baby. The relevant statistics favoured the former, and this is what she was offered and underwent; however unfortunately the risk associated with that materialised. The Court ruled that a patient should have the right to choose based not only on the bald overall statistics of risk as they apply to a population, but rather on her/his personal interpretation of the weight she/he attaches to the risks. Even if vaginal delivery is statistically ‘better’ overall, if a patient considers the specific risk associated with that option undesirable she must be free to make an alternative choice.

This is highly relevant in the matter of PPE guidance. The analogy is that PHE is taking on the role of the ‘doctor’, and medical staff are the ‘patient’. The ‘treatment’ options are the various forms of PPE. The statistical analysis available to PHE might well indeed suggest that a certain level PPE is most appropriate for one situation, and another level PPE for another, etc. However, as Montgomery stated, this is irrelevant. Rather, if the logic in the foregoing paragraph applies, then individual medical staff have the right, as much as any other patient, to choose their preferred level of PPE as based on the weight they personally attach to the risks involved. Regardless of any numerical risk estimates, someone required to undertake a particular task may be most reassured only by the maximum protection available, and is unlikely to accept something that is deemed statistically 'good enough'. Equally, in different scenarios we might see different choices being made. Some staff may prefer the maximum level PPE, while others a much lower level. Choices will inevitably be influenced by a cost-benefit balance: the ‘cost’ of wearing high levels of PPE being not just the financial cost, but the effort, discomfort and constriction imposed by that choice.

In fact, financial costs or resource limitations are also not relevant. They were not relevant in Montgomery; the statistical view that vaginal delivery was better was itself in part a resource-based judgement (and arguably a correct one, in purely scientific/statistical terms). Regardless, the Court ruled that this was not something that should supervene, but individual choice and rights were more important than cost.

Indeed, since staff are themselves experienced and knowledgeable, it is likely we will see a ‘wisdom of the crowds’ emerge. Naturally, through their collective choices, we will discover for which scenarios staff generally choose one form of PPE vs. another, and this data in turn could feed back to influence future guidance. It is most unlikely that staff will consistently select the highest-level (and hence most expensive) of PPE for all their tasks, as this will be uncomfortable and inhibit activity; more likely they will make sensible choices based on the available information and what matters to them.

Re-phrasing the PPE guidance

If this approach is accepted, it offers an opportunity to re-phrase the existing guidance. Rather than say “Wear X in situation A etc.”, as it does now in various tabular forms, the current advice could be phrased as follows:

- A clear statement of the available levels of PPE and their estimated degree of protection, as well as an explanation of the limitations of each (e.g. effort, restrictions of movement, cost, etc.).

- A list of example procedures/tasks and the estimate of their relative risks.

- A ‘best analysis’ attempt to match the two and offer the statistically-rational advice. Note that this will inevitably have grey areas where PHE will have to concede that there is no evidence, or that the estimated numerical value of risk between the options is very small.

- Most importantly, a statement that it is staff choice as to which of the types of PPE individuals wear for which procedures, and that staff should exercise that choice based on the best information available using 1 - 3 above.

Conclusions: what happens as COVID-19 incidence declines?

Adopting the suggested approach will change the language from one of binary decisions (‘”X is appropriate and Y inappropriate”) to a more sensible description of choice, risk and benefit. In a situation with so many uncertainties, it will empower staff through exercise of their choice – and hence restore confidence in the process.

The advantage of this new approach will be seen especially as the incidence of COVID-19 declines, when it will be a disease carried but less prevalent within the community. The statistics will change. Although the absolute risk of adverse consequences after contact will remain the same, the relative risk will be smaller. Because current PHE advice is didactic, it is difficult to see how this can suddenly change. In contrast, the new approach would continue to allow risk-averse staff to choose high level PPE, whilst empowering the majority to conclude that it is time to prioritise comfort over the now-reduced relative risk (i.e. they will correctly perceive the ‘gain’ of high level PPE as statistically marginal). Flying or driving a car could be much safer than they currently are, but we trade that off against things like comfort and convenience; and in the same way we will have to learn to live with COVID-19.

Professor Jaideep J Pandit

Consultant Anaesthetist Nuffield Department of Anaesthetics

Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust