Single use airway devices:

Harms and solutions

Annually the NHS in England procures and disposes of 32.3 million (m) airway devices

purchased for £56.9m. These devices are used for general anaesthesia and includes 18m

supraglottic devices (SGDs), 5.3m endotracheal tubes (ETTs), 4.4m tracheostomy tubes and

2.9m laryngoscope blades. Here we discuss the origins of single use airway devices and

suggest routes toward responsible and sustainable alternatives.

Most airway devices are made of plastic. Plastic became widely available in the 1960s and as a material offers many advantages:

it can be made flexible or rigid, is airtight, waterproof and cheap. However plastic manufacture is characterised by the extraction,

refinement, combustion and dispersal of organic hydrocarbons (oil) and their polymers, with the addition of plasticising chemicals

(typically phthalates or esteric aromatic compounds) to soften the finished product. The manufacturing process takes refined oil

as both substrate and energy source, emitting pollution in the form of carbon dioxide and particulate matter. In the UK airway

devices are typically used once and disposed of in energy and carbon-intensive waste streams (typically incineration), emitting

further carbon dioxide.

Most disposable laryngoscope blades are manufactured from steel, in northern Pakistan, and aligned with the principle of cost

reduction, this includes the use of sweatshops, child labour, and welding equipment with limited personal protection [1].

Single use and the airway

Association of Anaesthetists current guidance states that

laryngoscope blades and handles, ETTs, SGDs and oro/

nasopharyngeal airways must be high-level disinfected or

sterilised as these devices may become contaminated with

blood, occasionally breaching a mucosal barrier [2]. The

guidelines encourage the procurement of single use devices

(SUDs).

A significant factor in the historical move to single use

laryngoscope blades was the identification of variant CreutzfeldJakob disease (vCJD) caused by a prion protein that can reside

in oropharyngeal lymphatic tissues of those with end-stage

vCJD. Continued use of SUDs has been perpetuated by the

fact that the single use approach eliminates other infection

risk, including the transmission of respiratory pathogens. SUDs

also offer convenience and alleged cost savings compared to

reusable devices, especially where the infrastructure to enable

devices to be reused is lacking (many hospitals lost sterile

services capacity during the vCJD scare).

At present, most airway devices in the UK are single use. A

survey of hospitals in the UK showed that 95% (21/22) used

single use laryngoscope blades [3]. Most other airway devices

are also single use, although reusable SGDs, laryngoscopes

and videolaryngoscopes are commercially available. The notion

of single use has even extended to flexible bronchoscopes,

described as a possibly cost-effective solution: apparently

through avoiding costs of repair, reprocessing, maintenance and

risk of litigation.

Whilst we agree that it would be unacceptable to compromise

safety in favour of an improved environmental profile, we need

to re-appraise the belief that single use airway devices are best.

Myth 1: Re-use is an infection risk

A recent review found a lack of evidence to support the

argument that SUDs reduce the incidence of nosocomial

infections [4]. In the 1970’s there were a few cases of

transmission of vCJD between patients linked to neurosurgical

equipment and predated sterilisation, but vCJD has never

knowingly been transmitted by airway devices. Testing of over

62,000 tonsil specimens in the UK has never found evidence

of prion protein [5], and in England and Wales, tonsillectomy

has been performed using reusable instruments and steam

sterilisation since 2001 [6]. It seems nonsensical to not apply the

same approach to airway devices. The UK National Prion Clinic

agrees, and they advise: ‘For patients who are not suspected

to have prion diseases we don't think there is a requirement for

single use anaesthetics equipment’ [7].

Nevertheless, contaminated laryngoscope blades have been

linked to the deaths of critically ill patients [8] and a lack of

standardised reprocessing procedures was previously a

recognised concern [9, 10]. This does not mean that we need

SUDs, rather it means that we should explore reliable methods

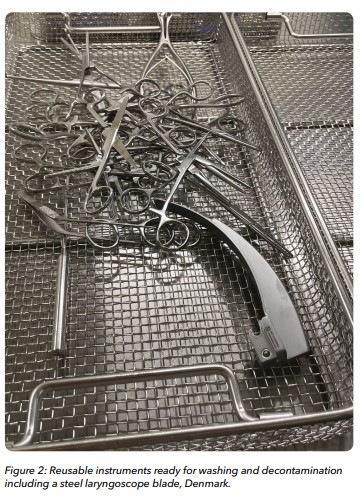

for decontamination and sterilisation. In other settings, steam

sterilisation and the reuse of laryngoscope blades are the norm.

Contrary to myth, disposable laryngoscopes carry a greater

bioburden when compared with reusable sterilised devices.

Disposable laryngoscopes are disinfected rather than sterilised,

with thresholds of acceptable bioburden set by manufacturers

in accordance with international standards (ISO 11737-1).

Importantly however there has been no study comparing

infection rates between reusable and disposable laryngoscopes.

Airway interventions are inherently non-sterile procedures

and involve an anaesthetist in non-decontaminated attire

and gloves; the source of infection may be independent of

laryngoscope type.

Myth 2: Single use is better for the environment

Multiple studies show the general principle that reuse of

medical equipment is better for the planet, the same is true

for airway devices. Single use plastic laryngoscope handles

represent up to 18 times the carbon footprint compared to

reusable steel [11]. Similarly, 40 single use SGDs have a lifecycle

carbon footprint of 11.3 KgCO2e, 1.5 times greater than a

reusable device used and decontaminated 40 times [12].

Myth 3: Single use is financially cheaper

In one study from Australia, the cost of using 4490 disposable

laryngoscope blades each year was estimated to cost £6000

more than using reusable equivalents [13]. A UK analysis

suggested reusable laryngoscope blades cost almost half that

of single use [14], and by extrapolation, this would save the NHS

£4.9m per annum.

The future

In summary, SUDs are costly for the public purse, the

environment and global society. Reusable alternatives to some

devices exist, with tried and tested reprocessing techniques to

ensure safety and reliability. However, there is a need for further

industrial and clinical research into reusable device design and

novel and reliable decontamination techniques. Alongside this,

we must advocate for national and international policy maturity,

away from over-zealous precaution and towards an evidencebased assessment of risk, that also considers planetary and

societal harm from the single use culture.

James Dalton

Anaesthesia Sustainability Fellow, University Hospitals Sussex

NHS Foundation Trust

Richard Newton

Consultant Anaesthetist & Environmental Anaesthesia Lead,

University Hospitals Sussex NHS Foundation Trust

Mahmood Bhutta

Chair of Ear, Nose & Throat Surgery & Professor of Sustainable

Healthcare, Brighton and Sussex Medical School

References

1. Bhutta M; Santhakumar A. Labour rights and violation in the manufacture of healthcare goods. ENT & Audiology News. 2015; 24: 1

2. Association of Anaesthetists. Infection Prevention and Control Guideline, 2020. URL: https://anaesthetists.org/Home/Resourcespublications/Guidelines/Infection-prevention-and-control-2020 (Accessed 06.11.2023)

3. Ghandi J; Campbell G. Unpublished data. Reusable vs single use infection control policy. Association of Anaesthetists Survey. 2022

4. Reynier T; Berahou M; Albaladejo P; Beloeil H. Moving towards green anaesthesia: are patient safety and environmentally friendly practices compatible? A focus on single-use devices. Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain Medicine. 2021; 40: 100907

5. Clewley J P; Kelly C M; Andrew N; et al. Prevalence of disease related prion protein in anonymous tonsil specimens in Britain: cross sectional opportunistic survey. British Medical Journal. 2009; 338: b1442

6. Clarke M B; Forster P; Cook T M. Airway management for tonsillectomy: a national survey of UK practice. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2009; 99: 425–428

7. UK National Prion Clinic (University College London) email to J Gandhi (Association of Anaesthetists) 07 April 2022

8. Jones B L; Gorman L J; Simpson J et al. An outbreak of Serratia marcescens in two neonatal intensive care units. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2000; 46: 314-319

9. Negri de Sousa A C, Levy C E, Freitas M I. Laryngoscope blades and handles as sources of cross-infection: an integrative review. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2013; 83: 269-275

10. Machan M D. Infection control practices of laryngoscope blades: a review of the literature. American Association of Nurse Anesthesiology. 2012; 80: 274-278

11. Sherman J D; Raibley 4th L A; Eckelman M J. Lifecycle assessment and costing methods for device procurement: comparing reusable and single-use disposable laryngoscopes. Anaesthesia & Analgesia. 2018; 127: 434-443.

12. Eckelman M; Mosher M; Gonzalez A; Sherman J. Comparative life cycle assessment of disposable and reusable laryngeal mask airways. Anaesthesia & Analgesia. 2012; 114: 1067–1072.

13. McGain F; Story D; Lim T; McAlister S. Financial and environmental costs of reusable and single-use anaesthetic equipment. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2017; 118: 862-869

14. Unity Insights & Kent Surrey and Sussex Academic Health Sciences Network. Carbon savings laryngeal blades and suture kits, 2022.

15. URL: https://unityinsights.co.uk/our-insights/carbonsavings/#:~:text=On%20the%20carbon%20emissions%20 front,52%25%20and%2090%25%20respectively (Accessed 06.11.2023)