Blood and Blocks: Nerve Blocks in Anaesthesia

In August 1810, novelist and diarist Frances (Fanny) Burney feels a small, annoying pain in her right breast. She dismisses it as nothing to worry about but her friends and husband are concerned. Only after some badgering by her nearest and dearest does she agree to see a doctor, whose treatment regimen proves to be ineffective.

Frances Burney Credit: National Portrait Gallery

The pain gets worse and her husband, former military officer Alexandre D’Arblay, now insists on her seeing “the most celebrated surgeon of France,” Baron Antoine Dubois. After he examines Fanny, he and Alexandre talk for a long time in the next room, making Fanny feel quite anxious. When her husband finally returns, “his looks were shocking... his whole face display[ing] the bitterest woe,” Fanny writes later.

“When the dreadful steel was plunged into the breast – cutting through veins – arteries – flesh – nerves – I needed no injunctions not to restrain my cries. I began a scream that lasted unintermittingly during the whole time of the incision – & I almost marvel that it rings not in my Ears still! So excruciating was the agony.”

Fanny was diagnosed with breast cancer and “formally condemned to an operation.” The first general anaesthesia for surgery was given in 1846, thirty-six years after Fanny’s diagnosis. She would have to expect at an operation during which she would be more or less fully conscious without any pain relief whatsoever available. Unsurprisingly, for this she felt “no courage,” and only consented to an operation after the pain in her breast got very severe and any other treatments, of which she tried many, were all unsuccessful.

The operation took place on 30 September 1811 in the family’s salon, performed by seven scary-looking, intimidating men in black. A year after the procedure, Fanny found the strength to write an extraordinary letter to her sister and friends at home, describing her ordeal in great detail:

“When the dreadful steel was plunged into the breast – cutting through veins – arteries – flesh – nerves – I needed no injunctions not to restrain my cries. I began a scream that lasted unintermittingly during the whole time of the incision – & I almost marvel that it rings not in my Ears still! So excruciating was the agony.”

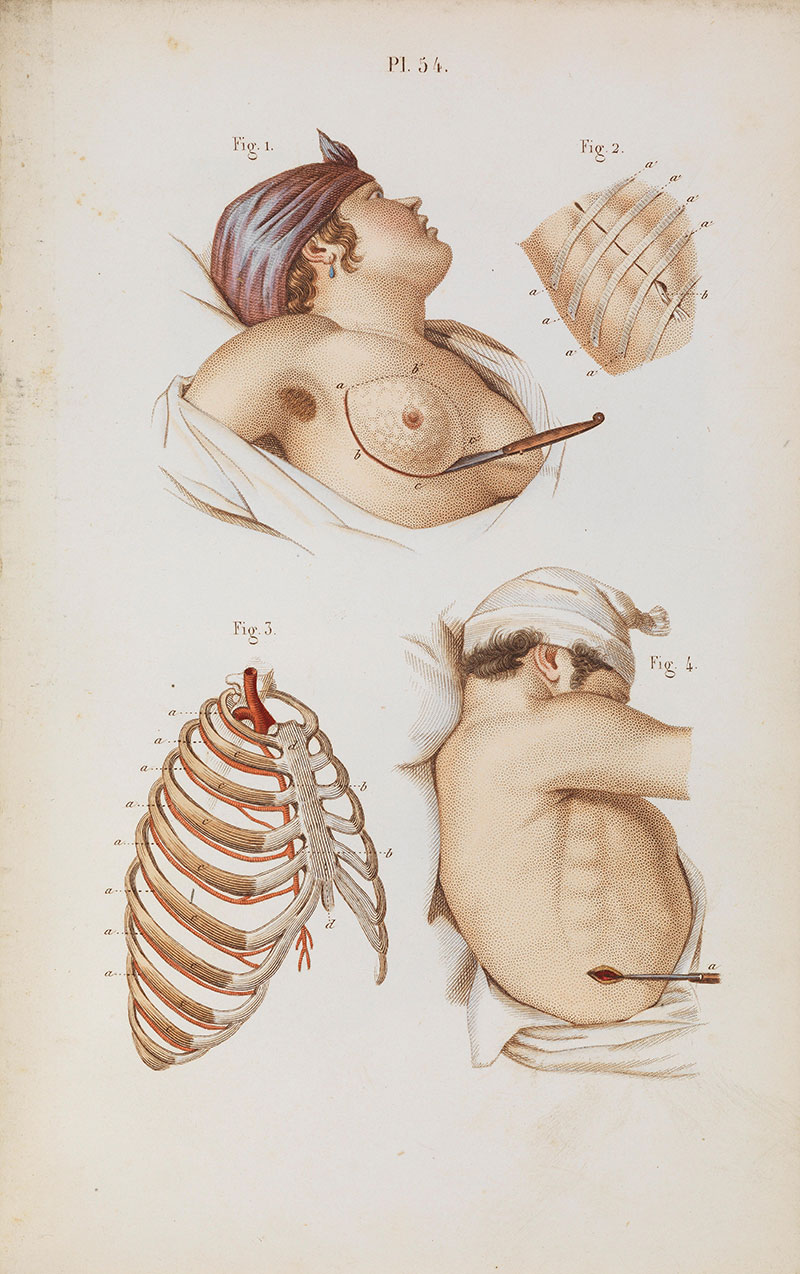

Illustration by Claude Bernard(1813-1878), French physiologist Credit: Wellcome Collection

A devastating diagnosis to receive in any time period, it is difficult to imagine anyone going through physical torment of this kind. Breast cancer remains the most common cancer in women, and is still the most common cancer in the UK in general. Thousands of people, not exclusively breast cancer patients, undergo surgery in the region of the breast and armpit every year. In many cases, these procedures cause significant acute pain and sometimes even chronic pain states. These patients, as well as those undergoing any procedures involving the chest wall in general, benefit from thoracic nerve blockade to reduce postoperative pain.

Breast operation and instruments Credit: Wellcome Collection

In the last decade’s most cited article in Anaesthesia, R. Blanco, T. Parras, J. G. McDonnell, and A. Prats-Galino, outlined a new technique they named serratus plane block. It is described as a “safe and easily performed regional anaesthetic block,” which provides complete pain relief of the lateral (side) part of the thorax (chest), and potentially causes fewer side effects. To achieve this, the researchers used a portable ultrasound device to identify the precise position of the nerves they wanted to target.

Ultrasound was introduced into regional anaesthesia fairly recently, although ‘ultrasonics’ had been used in medicine since the early 1940s. The introduction of the Doppler signal in 1978 meant that anaesthetists could now visually perceive nerves, helping with needle placement. Local anaesthetic spread could be visualised from 1989. This increased many anaesthetists’ confidence in performing regional blocks, as previously they either had had to possess incredibly detailed anatomical knowledge, or rely on colleagues who were specialists in regional anaesthesia. Now, recognising the technique’s advantages and with ultrasounds readily available, regional anaesthesia has become a core skill for every anaesthetist.

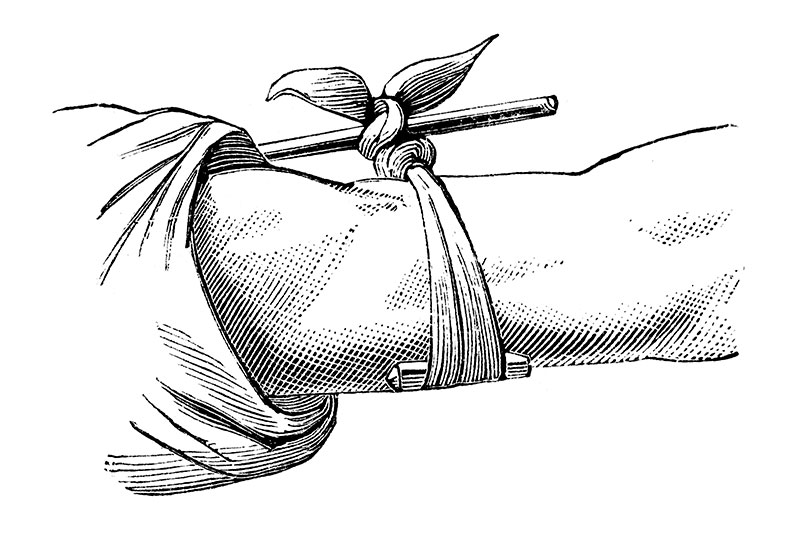

Local and regional anaesthesia have come a long way from their earliest methods, which included freezing or nerve compressions; reports of the numbing effect of both go back to antiquity. Fun fact: one of the doctors operating on Fanny Burney (and her favourite), Baron Dominique Jean Larrey, used the freezing method for amputations on the battlefields of the Napoleonic wars.

The advent of anaesthesia meant that enduring immense physical pain was perhaps one less thing to worry about for patients facing an operation, also allowing surgeons more time for their handiwork, on which they were now able to focus properly, without distracting screams.

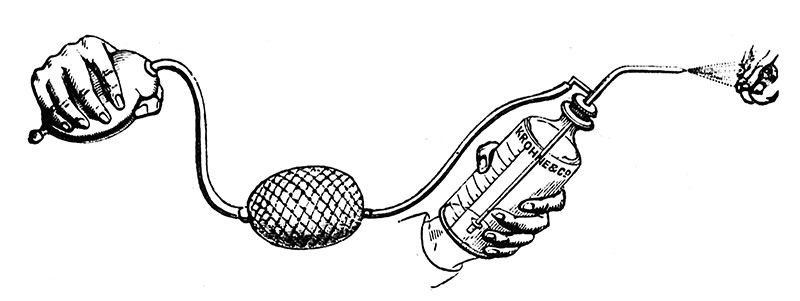

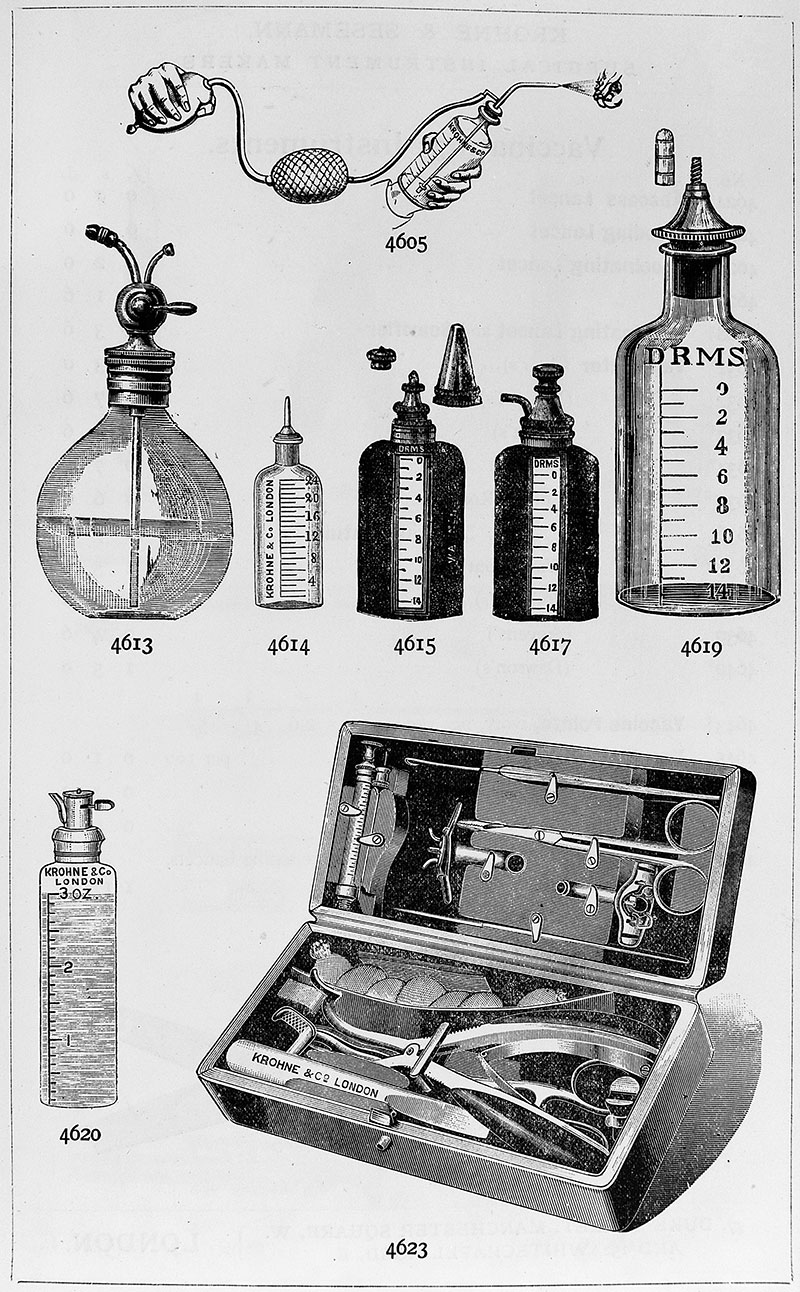

The first effective local anaesthetic was Benjamin Ward Richardson’s ether spray, which, however, was of limited use. Only the (re)discovery of cocaine’s anaesthetic properties in 1884 made more complex procedures viable. Thanks also to the development of hypodermic syringes and needles in the 1850s, it was now possible for local anaesthetic to be injected directly into a nerve. After much self-experimentation, the first spinal blocks were performed around the turn of the century.

Illustration of tourniquet

Richardson's ether spray Credit: Wellcome Collection

Richardson's ether spray equipment Credit: Wellcome Collection

Despite fluctuating in popularity over the decades, regional anaesthetics are used for a wide range of procedures today, including mastectomies. As Blanco et al have shown in their research, patients who undergo surgery using blocks such as the serratus plane block experience less postoperative pain than those who had been under general anaesthesia. Generally, patients will have a quicker recovery too, which is the hope of every practitioner.

The advent of anaesthesia meant that enduring immense physical pain was perhaps one less thing to worry about for patients facing an operation, also allowing surgeons more time for their handiwork, on which they were now able to focus properly, without distracting screams. Doctors have striven to make procedures both more effective and safer for those whose lives can be dramatically improved or even saved through an operation. Anaesthesia hugely contributed to safer, more successful operations and anaesthetists have continued to develop equipment, drugs, and techniques to make procedures as well as recovery more comfortable for patients.

Sonography guided femoral block

Fanny Burney’s operation only lasted twenty minutes, but, suffering unimaginable pain, must have felt like a lifetime. Yet, “all ended happily” for her; not only did she survive the procedure, she lived on for another twenty-nine years until she died in 1840, at the ripe age of eighty-seven.

If you would like to know more about the history of local and regional anaesthesia, view the Heritage Centre’s past exhibition Comfortably Numb on this topic.