Drills and algorithms: Managing difficult tracheal intubation in obstetrics - a blog post from the Heritage Centre

On 19 January 1847, Sir James Young Simpson administered ether to relieve pain in labour and recorded the first use of anaesthesia for childbirth. This was just three months after William Morton’s recorded use of ether for surgery.

Born in Bathgate, West Lothian, Simpson entered Edinburgh University aged 14 to study classics, changing to medicine in 1827. He qualified at 18 and studied obstetrics, gaining the MD in 1832. He progressed rapidly in midwifery, was elected President of the Royal Medical Society in 1835 and became a recognised authority on diseases of the placenta. In December 1839, he was elected by one vote to the Edinburgh chair of midwifery and hundreds attended his lectures.

Simpson practiced hypnotism but introduced ether inhalation to relieve labour pains in 1847. Unsatisfied with ether, which had a pungent smell and was flammable, Simpson began looking for an alternative which was more pleasant to inhale and provided a quick induction.

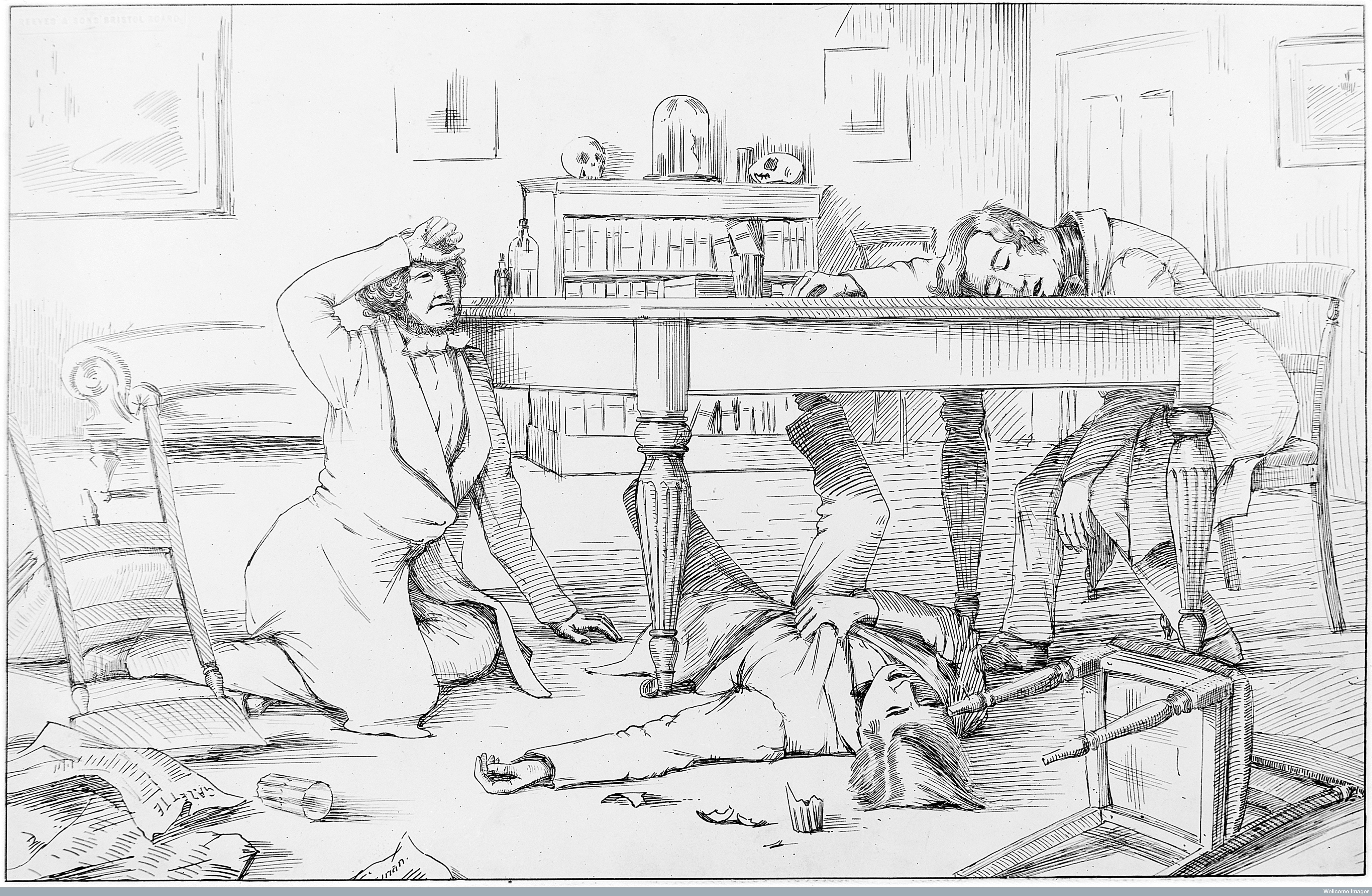

The dinner party where the effects of chloroform were discovered by Simpson and his assistants, 4 November 1847.

Self experimentation with chloroform and observations of others using it recreationally helped Simpson recognise the advantages of it for pain relief in labour and for surgery. On the 5 November 1847, just one day after the infamous dinner party, Simpson used chloroform during labour. This became the agent of choice for obstetrics until the 1870s in England, and the early 1900s in Scotland. This was despite complications with its use; it was easy to administer an overdose, it produced irregular heartbeats and even heart attacks.

The rest of the nineteenth century saw attempts to alleviate pain in labour by means other than inhalation anaesthetics, this included morphine and morphine like drugs.

From the 1930s, methods of analgesia which could be administered by midwives when a doctor was not present were developed. In the UK by this time, midwives delivered around 50% of normal births. Liverpool anaesthetist R.J. Minnitt’s developed the ‘Minnitt Machine’ in 1936, which provided a set mix of nitrous oxide and air for labour pain relief. The mother could self-administer the mixture whilst under the supervision of the midwife.

The machine was a step forwards in providing labour pain relief, but malfunctions with the apparatus meant it was largely abandoned by the 1950s.

In the 1950s, trichloroethylene (Trilene) was administered via specifically designed vaporizers, and was approved for use by midwives in 1954.

The ‘Cyprane’ Trilene Vaporizer, c.1954.

Epidural anaesthesia has become common in childbirth since the 1960s.

Whilst these techniques, equipment and agents provided relief from labour pain, they also presented some problems for either mother and, or, baby. However, general anaesthesia for women in labour presented more problems, with increased difficulty of tracheal intubation as a result of the anatomical, physiological and hormonal changes to a woman’s body during pregnancy.

The paper, Difficult Tracheal Intubation in Obstetrics published in Anaesthesia in November 1984 was that decades most cited article. It reviewed and discussed recent analysis which showed that in obstetrics, the main difficulty during laryngoscopy was the inability to see the vocal cords. This was because as the laryngoscope blade was lowered the epiglottis descended and hid the cords, which meant intubation had to be done blind using the ‘Macintosh method’, named after Dr Robert Macintosh.

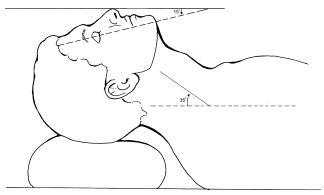

The other common difficulty cited was that beginners did not put the patient's head in the Magill ‘sniffing’ position. This recommended positioning of the head and neck before intubation was first published by Dr Ivan Magill in 1936. He described it as the position a person would take, ‘when sniffing the morning air’

The sniffing position

Passing an endotracheal tube before the introduction of curare into anaesthesia in the 1940s was very difficult. Curare was used as a muscle relaxant, which eased laryngeal reflexes and aided intubation. Dr Macintosh stated that, “The ability to pass an endotracheal tube under direct vision was the hallmark of the successful anaesthetist. Magill was outstanding in this respect.”

In 1943, Macintosh introduced the Macintosh Laryngoscope which had a curved blade. Prior to this, blades were straight, and the blade was used directly to hold the epiglottis.

Laryngoscope developed by Dr Ivan Magill.

Much of the credit paid to Macintosh’s laryngoscope was for the development of the curved blade. However, as he explained, the important aspect was that the tip did not pass the epiglottis and that the laryngoscope was properly used. In his own words, “The important point being that the tip finishes up proximal to the epiglottis. The curve, although convenient when intubating with naturally curved tubes, is not of primary importance.”

The flange design feature, which ran along the left lower edge of Macintosh’s blade, improved the ease of intubation. It moved the tongue to the side, which improved the view of the larynx and made more room for an endotracheal tube.

Macintosh Laryngoscope c.1943

Whilst improvements with equipment aided intubation the Difficult Tracheal Intubation in Obstetrics article evidences that difficulties were still faced. The article cited the use of drills as an integral part of an anaesthetists training to reduce maternal mortality. The three main drills concerned, difficult intubation, failed intubation, and the correct use of cricoid pressure, all of which they noted, “…need as much attention as the cardiac arrest drill, but whether they always get it seems doubtful at present.”

The failed intubation drill quoted was devised by Dr Michael Tunstall. In 1976, Dr Tunstall suggested a failed intubation drill for caesarean section. This drill was the first of its kind and a significant step in the role anaesthesia played in reducing maternal mortality.

Tunstall's drill became part of an anaesthetist’s training, with every final Fellow of the Faculty of Anaesthetists of the Royal College of Surgeons (FFARCS) examination candidate expected to repeat the drill word for word.

Tunstall’s first contribution to obstetric anaesthesia actually came whilst he was a trainee with the development of Entonox. Nitrous oxide and oxygen were stored as liquid and gas respectively, and came in four cylinders (two plus two spares). In the late 1950s, Tunstall developed the idea of pre-mixing the oxygen and nitrous oxide in one cylinder, which would also deliver a constant mixture of the agents. So it was that Entonox was developed and introduced for labour analgesia by the British Oxygen Company (BOC). Dr Tunstall first used it clinically at The Royal Hospital, Portsmouth in 1961.

Another benefit of the Entonox cylinders was they could be easily transported, and small ones were produced for home deliveries. The apparatus comprised of demand valves, a pressure reducing valve, a cylinder contents gauge, and a non-interchangeable pin-index system to prevent the administration of the wrong gas.

The liquids would layer if left standing for a long time, and this process was accelerated by low temperatures. A gentle rocking in a warm room can solve the problem.

Compact and portable apparatus with Entonox, (premixed 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen) cylinder. The mask is applied tightly to the face. A pressure gauge indicates the quantity of gas mixture in the cylinder.

Concerned about the high level of patient awareness with recall (AWR) associated with general anaesthesia for caesarean section Tunstall developed the ‘Isolated Forearm’ technique in 1977. The technique consisted of inflating a padded cuff/tourniquet around the right upper arm before giving any neuromuscular blocking drug (NBD), it was deflated shortly after delivery when anaesthesia was deepened. Tunstall also researched methoyflurane as an inhalational analgesic, and helped colleagues develop one of the first neonatal intensive care units. A truly eminent obstetric anaesthetist, he was President of the Obstetric Anaesthetists’ Association (OAA) (1987-1990) and received their Gold Medal in 1990.

Moving forward several decades and in 2012 the OAA and Difficult Airway Society (DAS) committees established a working group to develop national guidelines on the management of difficult airway in obstetrics in the UK. This came at a time of declining numbers and experience in obstetric general anaesthesia.

Following extensive work, the Guidelines for the management of difficult and failed tracheal intubation in obstetrics was published in Anaesthesia in 2015. The guidelines contain four algorithms and two information tables. The guidelines were produced to improve consistency of clinical practice, reduce adverse events and provide a structure for teaching and training on failed tracheal intubation in obstetrics.