Controlling the Aspera Ateria: A Short History of Airway Management – a blog from the Heritage Centre

On average, we take around 20,000 breaths every single day. Breathing in through our nose or mouth, air flows through our throat and windpipe (trachea) into our lungs. It’s something most of us are lucky enough to do without thinking about it. Yet, when breathing does become really difficult or even impossible, the pathway through which air travels into the lungs – the airway – needs managing.

Tracheotomies were performed in emergencies in ancient India, Egypt, and Greece alike, suggesting that by 1000 BC, it had become a routine procedure.

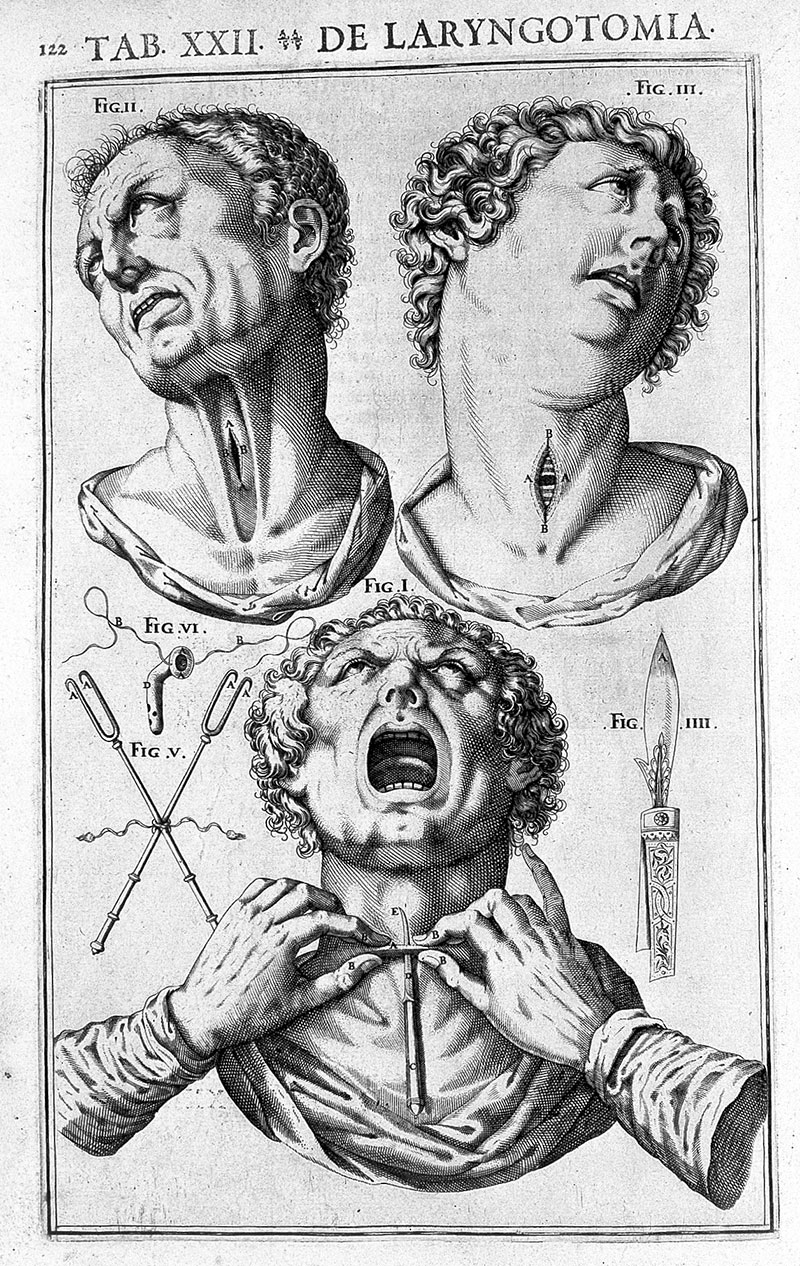

Our early ancestors were just as much aware of this as we are today, as accounts from the Bronze Age evidence. Tracheotomies were performed in emergencies in ancient India, Egypt, and Greece alike, suggesting that by 1000 BC, it had become a routine procedure. It appears that during the Middle Ages, however, the potentially lifesaving method went out of fashion. There are only few mentions of the operation, one terming it a “scandal of surgery.” Interest in tracheotomies only started to pick up again during the Renaissance, when countless experiments on animals were carried out.

Tracheotomy from Casserius, De Vocis Auditusque Organis Credit: Wellcome Collection

In 1546, Antonio Brassavola went a step further and performed the first successful (documented!) tracheotomy in a patient with a laryngeal abscess, who made a full recovery. The medical community quickly rediscovered appreciation for the procedure; anatomist and surgeon Girolamo Fabrici d’Acquapendente was convinced “the opening of the aspera arteria,” the artery of air, was one, if not the, most important operation of all, as “man is recalled from a quick death to a sudden repossession of life,” able to “resume an existence which had been all but annihilated.”

Some seventy years later, in 1620, French surgeon Nicholas Habicot published a treatise describing cases of successful tracheotomies and their dramatic back stories, such as that of a fourteen year-old boy who had swallowed a bag of gold coins to keep it safe from thieves, or that of a convicted criminal sentenced to be hanged, who hired a surgeon to perform a secret tracheotomy before his appointment with the executioner. They somehow concealed the tube that had been inserted, and he might have gotten away with it too, was it not for the unfortunate fact that the criminal’s neck broke.

Nicolas Habicot, Question chriurgicale, 1620

Tracheotomies had made a comeback, then. But what about endotracheal intubation and endotracheal anaesthesia? How were airways managed during anaesthesia? Endotracheal intubations were first used to resuscitate drowning victims in the 18th century. That, and rectal intubation but that’s a whole different story... In the early days of anaesthesia in the mid-19th century, anaesthetics were given via a mask, and since patients’ cough and swallowing reflexes remained intact, only little attention was paid to the management of airways.

After ever-curious anaesthesia pioneer John Snow had managed to anaesthetise a rabbit performing a tracheotomy on it, German surgeon Friedrich Trendelenburg administered the first endotracheal anaesthesia using the same method in a human in 1871. Only seven years later, Scottish surgeon William Macewen is believed to have performed the first orotracheal (through the mouth) intubation for chloroform anaesthesia – finally!

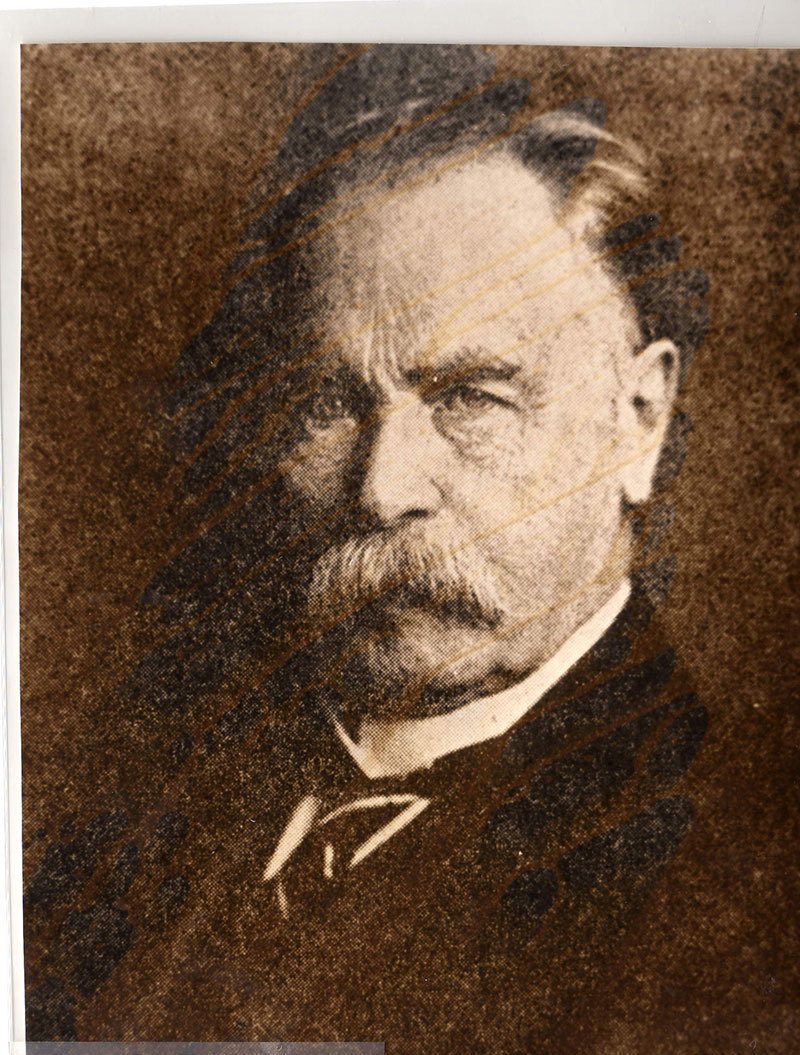

German surgeon Friedrich Trendelenburg

Trendelenburg cone

Trendelenburg cone

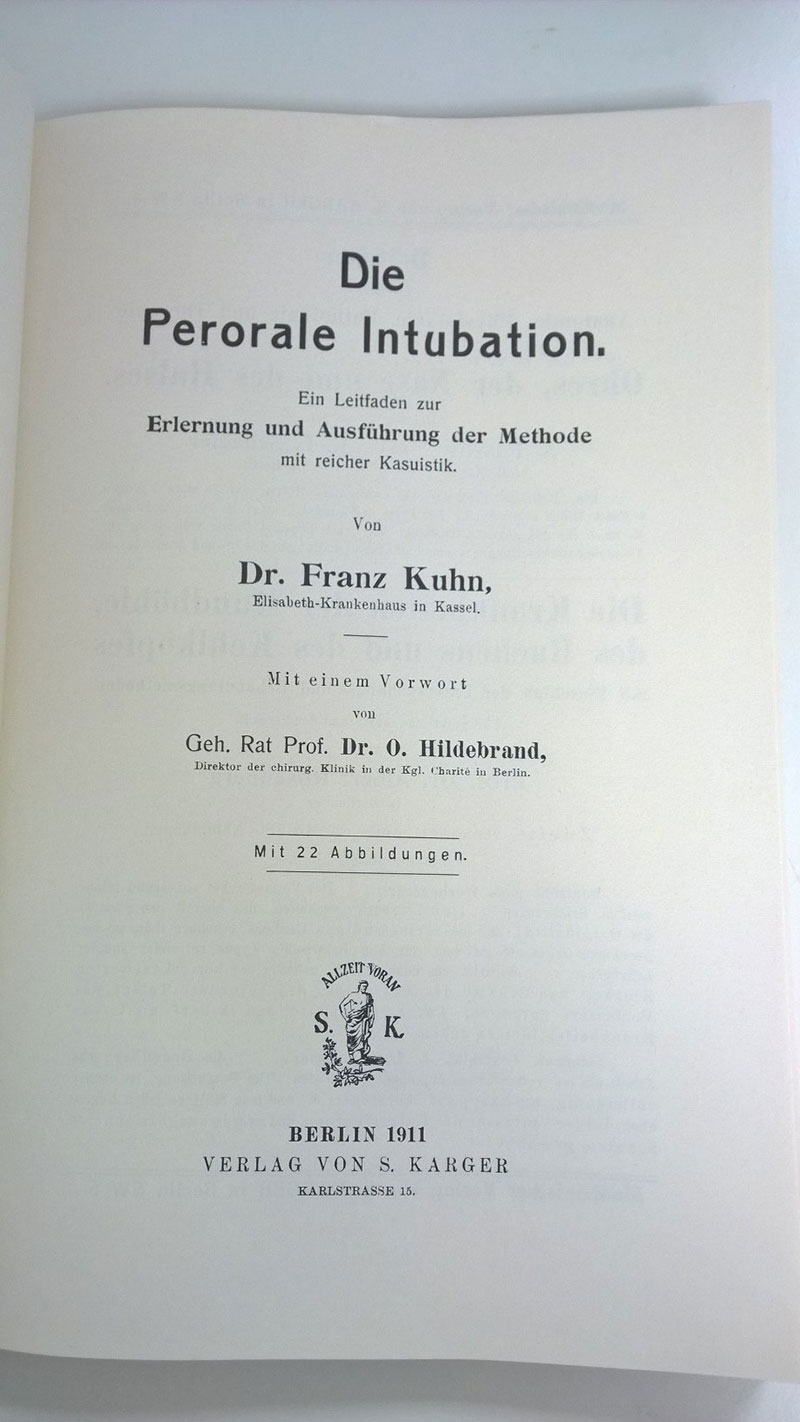

A physician is only as good as their equipment, right? It helps, at least. German surgeon Franz Kuhn was rather visionary at the turn of the twentieth century. Not only did he design metal tubes that could be inserted through the mouth even ‘blindly’ (without direct view of the larynx), he also described the use of a curved tube introducer, as well as being the first to publish a paper on nasal intubation, the tube for which, he argued, “lies better” and leaves the mouth free for any surgical procedures. Moreover, Kuhn appreciated the risk of spasm of the larynx and believed that ‘cocainization’ of it was helpful when intubating.

Paper by German surgeon Franz Kuhn

Kuhn endotracheal tube, 1901

Kuhn endotracheal tube

Endotracheal nasal tube set of 8

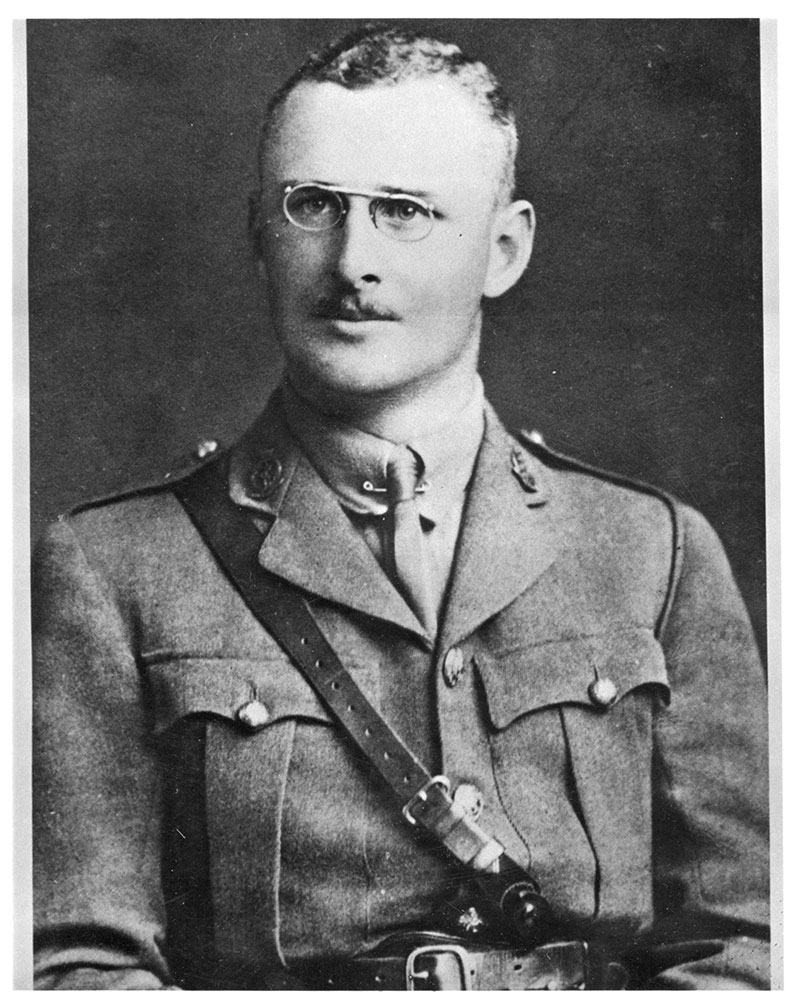

Enter Ivan Whiteside Magill. He was the (initially reluctant) anaesthetist at Queen’s Hospital in Sidcup, where facial injuries incurred in the First World War were treated. As such, masks and traditional breathing tubes were simply impractical. Developing a series of equipment as well as techniques for endotracheal intubation such as tubes, laryngoscopes, and forceps, he and his colleague Stanley Rowbotham conquered the airway problem.

Ivan Magill (far right) and house officers

Ivan Magill

Tongue forceps modified by Magill

Indirect laryngoscopy was first described by an English singing teacher in 1855, when he used sunlight and two mirrors to see his own vocal cords move. Direct laryngoscopy came along in 1895. Although fibreoptic intubation has become more common in the more recent past, the Macintosh curved laryngoscopic blade that was introduced in 1943 remains much beloved piece of equipment today.

Building on ancient knowledge, tracheotomy and tracheal intubation procedures have been refined in the last few centuries, resulting in the prevention of countless deaths.

Today, managing airways, ensuring a patient’s breathing is safe, is an anaesthetist’s bread and butter. With the knowledge and equipment available to them, as well as the rigorous training they go through, this has become much ‘easier’ over the decades and centuries. However, managing an airway is not always straightforward. This could be owing to a number of reasons, such as an injury or swelling of the airway, difficulty of opening the patient’s mouth, or indeed because of unexpected complications. In these very rare circumstances, anaesthetists can resort to the guidelines produced by the Difficult Airway Society (DAS), aiding them in these circumstances. DAS, formed in 1995, is the UK’s largest anaesthetic subspecialist society and committed to improving the standard of airway management as well as advance its public understanding.

The history of airway management is long and fascinating. Building on ancient knowledge, tracheotomy and tracheal intubation procedures have been refined in the last few centuries, resulting in the prevention of countless deaths. There is no doubt that further advances in techniques and equipment will be made to render airway management easier, ensuring that even if we need a little help with any of those 20,000 breaths we take every day, we’re as safe as we can be.